COP21: Putting the climate agreement into action: do the public support it?

François Hollande declared “history is here” when the most ambitious goal ever to be set around climate change was agreed upon in Paris in December last year. The much-anticipated accord surprised many just by being agreed – an achievement welcomed after the disappointing 2009 Copenhagen talks. While experts and activists will debate what was achieved and its implications for the environment and communities around the world affected by climate change, there are sighs of relief that negotiators and politicians from 197 countries agreed on something of substance.

But with the dust now settled on the agreement, and with many world leaders expected to sign the agreement on Earth Day in New York today, the challenge turns to making and implementing ambitious climate plans and convincing the public of their necessity. Understanding how the UK public think and feel about climate change is fundamental to addressing the issue; failing to account for how it (and policies to mitigate and adapt to it) affects people’s lives could lead to public apathy or worse, opposition, and ultimately threaten the commitments made. Today, it is more important than ever for the government to listen to the public – people are more likely to believe that the government acts in its own self-interest and not the British people’s than they were for most of the last 20 years .[1] So what do people think, and know, about climate change?

At Ipsos’s Social Research Institute, the Climate and Energy research team undertook research to understand what the British public know about climate, how concerned they are by it, and what they thought should be agreed upon in Paris[2]. The data were collected shortly before and during the conference, between the 27th November and the 2nd December 2015, and we have analysed this along with Ipsos tracking data spanning from 2005-2015.

Around 9 in 10 (88%) of the Great Britain population believe climate change is occurring, similar to the level recorded in 2005 (91%). However, we find that over this period the British public have become less concerned about climate change; 68% were concerned in 2014 compared to 82% in 2005[3]. Further, despite newly released evidence (April 2016) that 97% of environmental scientists are in agreement that climate change is anthropogenic, just 64% of the British population believes it is a result of human activity.[4][5] That around a quarter (24%)[6] of British people disagree that humans play a lead role in causing climate change – which could reasonably be considered the first step towards supporting a drive for a low carbon economy – suggests that getting public buy-in to the commitments made in Paris may not be plain sailing for the government.

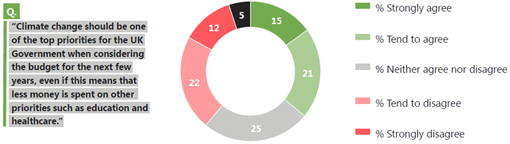

Nevertheless, our research suggests a relatively strong public mandate for action on global warming. Prior to the Paris conference, the majority of people thought the UK government should take a leading global role in tackling climate change (65% agree, 11% disagree). Most also believed that the government should sign up to a legally binding agreement on climate change (57% agree, 14% disagree). Of course, it is easy to support action when it doesn’t come at a readily-apparent cost. When people are asked to consider whether investment in combatting climate change should be at the expense of other priorities like education and healthcare, opinion is much more evenly split:

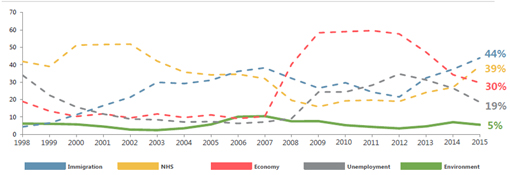

We also see this trade-off in Ipsos’s monthly Issues Index[7], where the environment is far down the list of what the British public spontaneously see as the greatest issues facing the country today. This suggests that, while most people would like to see action taken in response to Paris, environmental issues are only strongly salient for very few of us, which is likely to limit pressure from the public to see through the commitments, and particularly so where a trade-off with priority areas of spending is implied.

Increasing the salience of climate change? Climate change and immigration

One tempting route to increasing the salience of climate change is to tie it to issues far more at the forefront of the public consciousness, particularly those considered to be important. Our Issues Index has shown that immigration has been at the top of the British public’s concerns for almost a year (since June 2014), and has been one of the top two concerns since June 2014. The links between climate change and population displacement are well-documented[8], so could highlighting this link between climate change and immigration increase salience for those who are not traditionally climate advocates?

To test whether willingness to address climate change modifies when linked to immigration, the survey included a randomly allocated split sample experiment. Prior to answering questions about climate change, half of those responding to the survey were presented with a statement highlighting the possibility that global warming could lead to increased immigration – for example, through increased natural disasters, hunger and drought. The remaining half did not see this information.

Interestingly, this didn’t produce any substantial differences in willingness to address or prioritise climate change. Respondents were not asked explicitly about the link between climate change and immigration so the reasons for this absence of any effect aren’t clear – whether they do not accept the migration argument, require more detailed information behind this link, repeated exposure to this message or believe that other means of combating immigration are more important. Further research would be needed to explore this in more detail but, at a very surface level, it appears this particular route to increasing support for climate change would not be effective without a stronger or more convincing connection being made.

Climate change and the economy

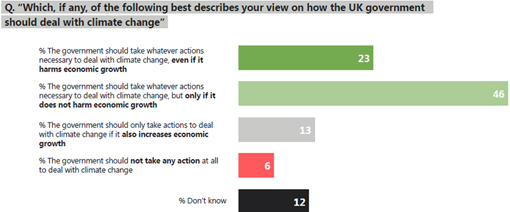

One factor that often does feature in arguments for and against taking action on climate is how it will affect the economy. Here, the most popular stance, taken by almost half of Brits, is to support action provided it doesn’t damage economic growth. So it will be important to demonstrate to the public that any proposed response to the Paris agreement doesn’t hurt the economy. Interestingly though, a substantial minority of people – almost a quarter of the population (23%) – are willing to see action taken even at the cost of growth, suggesting there’s quite a large constituency of ‘darker’ greens. So who are they?

Who is most supportive of action?

In general, those in younger age groups, those with a higher educational level, and those in higher socio-economic grades exhibit more pro-environmental attitudes. For example, when asked the question “The UK government should sign up to a legally binding agreement to combat climate change at the Paris Conference”, support increases as education levels rise; those with a degree or higher are more likely to agree (67%) than those with A-levels (54%), GCSEs (48%), and no formal qualification (38%).

Similarly, the question “Climate change should be one of the top priorities for the UK government when considering the budget for the next few years, even if this means that less money is spent on other priorities such as education and healthcare” also saw notable differences between demographic groups. For example, the two older cohorts are more likely to disagree with the statement than the three younger ones: 45-54 (40%) and 55-75 (41%) vs. 16-24 (24%), 25-34 (28%) and 35-44 (29%).

So if support for action on climate change is to increase further, it is older people and those with less education that the government and climate campaigners will need to work hardest to convince that commitments made in Paris should be turned into reality.

- This blog was written by Alexandra Palmqvist Aslaksen and Darren Fleetwood.

Technical Note:

- The survey was administered using an online questionnaire and representatively sampled 2,175 members of the British public aged 18-75. The fieldwork took place between the 27th November – 2nd December 2015.

- The sample was split randomly in half to test the experiment reported in the text above. The sample we have reported throughout the text is based on half of the respondents (1,168).

- Data are weighted to the national population profile by age, sex, working status, social grade, region, ethnicity, and tenure.

[2] Unless otherwise indicated, the data cited in this article are drawn from the following source: Ipsos, Base: 1,087 GB adults, aged 16-75, 27th November – 2nd December 2015. Methodology: online survey.

[3] Ipsos, Face-to-face in-home interviews. Bases: 2005: 1,491 GB adults, aged 15 and over, 1st October – 6th November 2005, 2014: 1,002 GB adults aged 16 and over, 28th August - 31st October 2014.

[4] Ipsos, Base: 16,039 adults across 20 countries (GB: 1,000), 3rd – 17th September 2013. Methodology: online.

[5] Cook, John, et al. "Consensus on consensus: a synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming." Environmental Research Letters11.4 (2016): http://iopscience.iop.org/article/10.1088/1748-9326/11/4/048002/meta

[6] The remainder could not provide an opinion either way or replied don’t know.

[7] Ipsos Issues Index. Base: c.1,000 GB adults aged 18+ per month. Data based on annual aggregates for each year, using January – November for 2015. Methodology: face-to-face in-home interviews.

[8] Reuveny, Rafael. "Climate change-induced migration and violent conflict." Political Geography 26.6 (2007): 656-673: http://n.ereserve.fiu.edu/010034609-1.pdf