How the pandemic has fallen most heavily on Americans of color

What you need to know:

- Health and economic outcomes have tended to be worse for Black and Hispanic Americans over the course of the pandemic. Ongoing tracking data from the Axios-Ipsos Coronavirus Index highlights disparities in proximity to the virus and overall economic stress between racial and ethnic communities.

- Though the United States gained back 4.8 million jobs in June, somewhat ameliorating the worst unemployment crisis since the Great Depression, the racial unemployment gap is now the widest it has been in five years. Even these gains may prove to be temporary as some states have had to pause or roll back their reopening plans.

- The current economic crisis and the underlying wealth gap are driving a level of protest and unrest not seen since the 1960s.

Deep dive:

The COVID-19 pandemic has been a time of national reckoning on many levels, but one of the starkest realities to be laid bare during this time is the disparity in the experiences between people of color and white Americans. COVID-19’s disproportionate impact on Black and Hispanic Americans is fueled by and exacerbating underlying inequalities that have long depressed health and economic outcomes for people of color.

A New York Times analysis of Centers of Disease Control (CDC) data offers the most comprehensive look available at the disproportionate health impact of the coronavirus on Black and Hispanic Americans. The statistics are chilling: Black and Hispanic Americans are three times as likely to have been infected with the virus, and twice as likely to die from the virus compared to white Americans.

While the CDC data used in this analysis was not complete as it included cases only up through the end of May – thus missing the new surge in cases through June and July – and did not include information about race and ethnicity in half the cases, its essential findings are mirrored in cities with demographic data available. In a particularly extreme example, Black residents make up 46% of the total population of Washington, D.C., but represented 74% of all coronavirus deaths in the District as of mid-July.

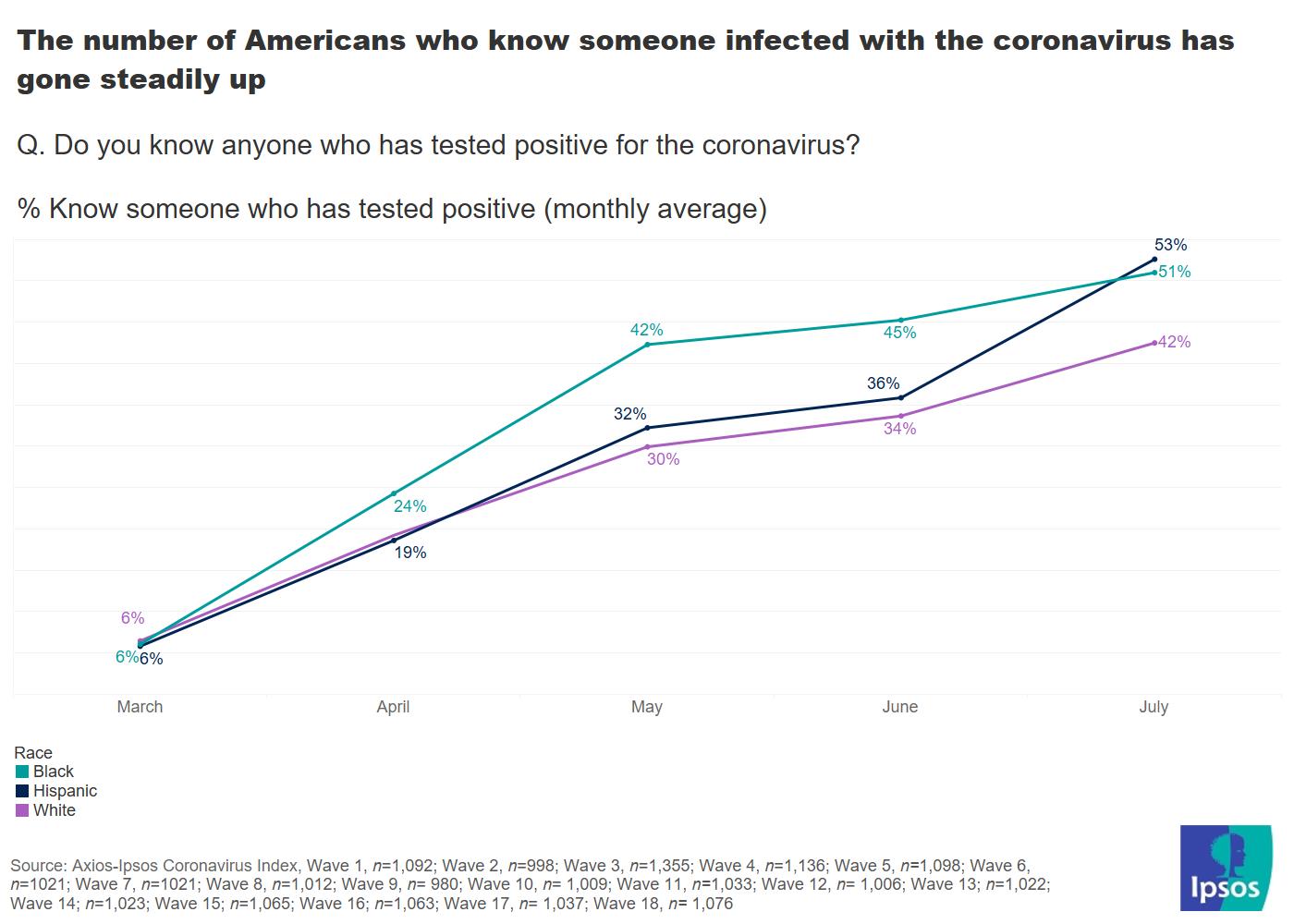

Similarly, the Axios-Ipsos Coronavirus Index, which has tracked the virus’ impact on American life for 18 weeks so far, highlights a clear racial divide in experience with the virus. While the number of Americans proximate to someone who has tested positive has grown steadily since people first grew aware of the virus’ presence in the U.S. in mid-March, Americans of color tend to be closer to people infected with the virus than their white counterparts.

While there are a host of factors contributing to the disproportionate infection and death rate among communities of color, one of the key underlying issues is economic inequality. Over the course of the pandemic, lower income and Americans of color have disproportionately been on the front lines of the crisis, continuing to go out to work to pay the bills despite the inherent health risks. People of color make up nearly 50% of the essential workers still on the job during the pandemic, many of whom continued to work to keep basic services functioning during the worst of the outbreak. While performing an enormous public service, they were also putting themselves at greater risk of contracting the virus.

The roots of race-based economic inequality run deep. Centuries of racial discrimination, not to mention chattel slavery, contributed to a fundamental wealth divide that still exists to this day. That leaves people of color more vulnerable to each economic downturn. Americans of color were also less likely to have been buoyed up by the economic gains of the post-Recession era, putting them at a disadvantage heading into the latest economic crisis. But even before the Great Recession and pandemic, which cumulatively precipitated the largest wave of mass unemployment since the Great Depression, Black and Hispanic Americans were already at a significant disadvantage.

In a nation already distinctive for its extreme wealth inequality, the racial wealth gap is similarly glaring. A Federal Reserve study found that the median net worth of a white family in America was $138,200 in 2016, compared to $17,600 among Black families and $20,700 among Hispanic families. The proportion of families with no or negative net worth falls along similar lines: 9% of white families, 19% of Black families and 13% of Hispanic families.

In light of these intersecting issues, it is not surprising that communities of color would consequently have less of a safety net to help them through the crisis. The weekly Axios-Ipsos Coronavirus Index underscores the sense of financial precarity felt by Black and Hispanic Americans over the course of the pandemic. Relative to white Americans they report being significantly more worried about the fundamentals, such as their job security and ability to pay the bills. Where two in five white Americans share these concerns, majority of Black (three in five) and Hispanic Americans (two thirds) are worried about these issues.

For a brief moment in late May and early June, it looked as though the nation had perhaps turned the corner on the virus. Infections and deaths were on the decline, and states judged it safe to lift restrictions. The official unemployment rate, after shooting up to 14.4% in April, fell back down to 11.1% in June once businesses began to open back up again. Hindsight being 20/20, that early opening now appears to have been premature as coronavirus cases surge. States had to pause or roll back their reopening plans as cases began to rise again as a direct consequence of reduced social distancing.

Even this relatively muted improvement in the employment outlook, temporary as it may ultimately be, did not benefit all Americans equally. The racial gap in unemployment is now the widest it has been in five years. From May to June, unemployment among Black Americans declined from 16.8% to 15.4%. Over the same period, the white unemployment rate fell from 12.4% to 10.1%.

These gaps demonstrate the extent to which the status quo was not working for millions of Black and Hispanic Americans even before the pandemic upended life as we knew it. General outrage and frustration are finding expression in the protests against George Floyd’s killing and in support of the Black Lives Matter Movement. Others, like the Strike for Black Lives, which mobilized thousands of workers in more than two dozen cities across the United States, are taking on economic inequality directly.

As Wellington Thomas, an emergency room technician at Loretto Hospital in Chicago and Strike for Black Lives participant, told Fortune magazine, “I’m going on strike for Black lives because our hospital isn’t taking our demands seriously when it’s literally a matter of life or death. We know COVID-19 has disproportionately affected Black lives here in Chicago and across the country. Our hospitals and elected leaders need to recognize that. That means investing in those of us serving Black communities with higher wages, better benefits, and safer staffing so we can continue to provide the quality of care our patients deserve.”

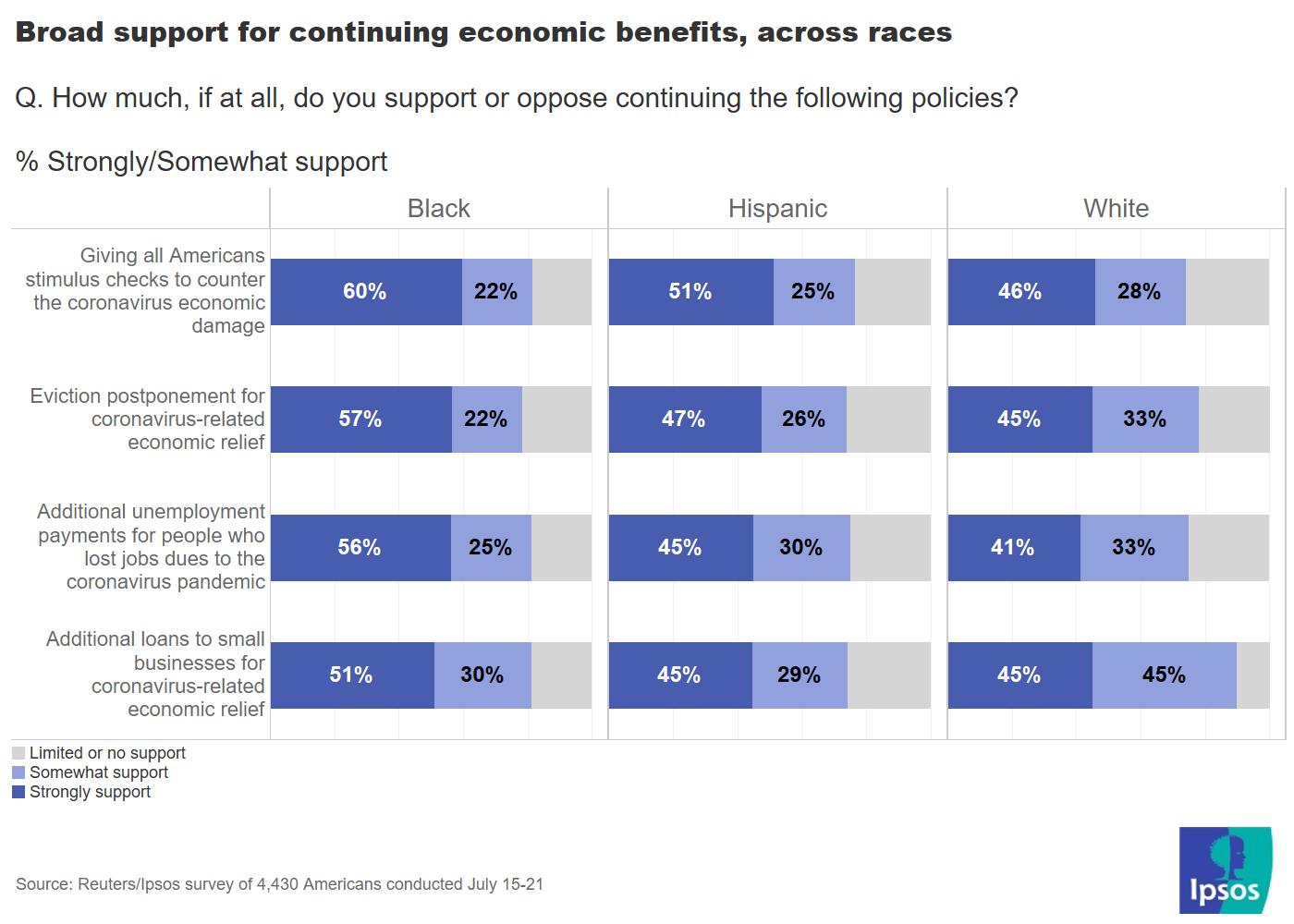

With the virus still far from contained, a full economic revival is not imminent. For the past several months, millions of Americans have been keeping their heads above the water with the help of a slate of federal benefits. Direct payments; a $600 boost to weekly unemployment checks; and the Payment Protection Program, designed to keep workers on the payroll, have helped keep the lights on and the bills paid. These benefits are set to expire on July 31st while Congress debates a second economic relief plan.

Americans across party and racial lines broadly support continuing these benefits. The question becomes, can Congress roll out a plan in time to prevent further economic fallout? As the past few months would indicate, if they fail to do so, the blow is likely to fall hardest on those already hardest hit. Without a new federal stimulus plan firmly in place to help those struggling the most, many Americans may find the ground beneath their feet giving way once again – and the ground underneath Black and Hispanic Americans’ feet is already disproportionately weak.