Global perspectives on inequality: What does it mean, who are we worried about, and how much do we care?

The inaugural Ipsos Equalities Index marks the first time that we’ve examined global attitudes to how people around the world understand fairness, how they perceive the discrimination experienced by different groups in society, how they assess the progress that has been made, and who they think should be responsible for improving the situation. It draws from, and connects back to, work we have already done – and we will be developing this study in the coming years so that we can keep track of how attitudes are changing.

Talking about our generations

Looking across 33 different countries in every part of the world, we found that younger people are more sensitive to inequality, with every successive generation more likely to see it as an important issue in their country. “Baby Boomers” (defined here as people born between 1945 and 1965) are the only generation where there isn’t a majority agreeing with this. We also see that younger generations are increasingly sceptical about the idea that they live in a meritocracy, and are increasingly likely to believe that structural factors (ie things that they, on their own, can do very little about) are more important in determining how successful they will be in life. They are also more likely to think that a truly fair society is one which delivers the same quality of life to every person within it, rather than simply offering equal opportunities to all. Because this is the first time we have run this study, we don’t yet know whether this is because of the circumstances that each generation has grown up in (known as a “cohort effect”), or simply because of how old they are now (the “lifecycle effect”) which would mean individual attitudes are more likely to change in the future.

All that said, there are some notable exceptions to these trends, including around age and gender. Perhaps unsurprisingly, younger generations are considerably less likely to say that old people are unfairly treated in their society (we found that older people reciprocate), and “Generation Z” (those born between 1996 and 2012) are the only generation to think that young people are more poorly treated than senior citizens.

The second exception to the general trend concerns gender equality, where we discovered that younger people are not significantly more likely to think that women suffer from unfair treatment. But a signal which complements some of our discoveries in our International Women’s Day survey from earlier this year is the growing sense among younger people that men are unfairly treated. Although only a small minority of people think this (just 8% of Generation Z), but there is a clear trend when we look along the generations: Baby Boomers are only half as likely to hold this view.

Men and women: on different planets

When we compare what women told us with what men told us, we see that there is a significant difference in attitudes towards the treatment of people with disabilities, the neurodivergent, those suffering with poor mental health, and those who identify as LGBT+: in every case, women are more likely than men to view these groups as victims of unequal treatment.

Again, it was no great surprise to see that women are considerably more likely than men to see women as unfairly treated, and men are much more likely than women to think that men are unfairly treated.

But when we asked about ageism, religious prejudice, racism, and xenophobia, there is no significant difference between how men and women view these issues.

Racism: in the spotlight or in the shade?

The long imprint left by historic injustices is very clear in our data: countries where significant indigenous populations have been displaced (such as New Zealand, Peru, Brazil and South Africa), those with a history of racialised chattel slavery and/or legalised discrimination on racial grounds (such as the United States, South Africa and Brazil), and those with a high degree of ethnic diversity (such as Indonesia and the Netherlands) tend to be more sensitive to this issue. Conversely, countries that are ethnically more homogenous (such as Japan and South Korea) are much more relaxed about it.

Knowledge is not bliss

On the face of it, one of the more surprising findings was that wealthier people, and those with more education – who one might imagine were less likely to suffer the ill effects of inequality – are actually more concerned about it, and also say that efforts to reduce or repair it need to go further.

Less surprisingly, these groups are more likely to agree that equality of opportunity is the defining characteristic of a fair society, and are marginally less likely to be drawn to concepts of “equity” (we described an equitable society as one where everyone enjoyed the same quality of life)

Perils of perception

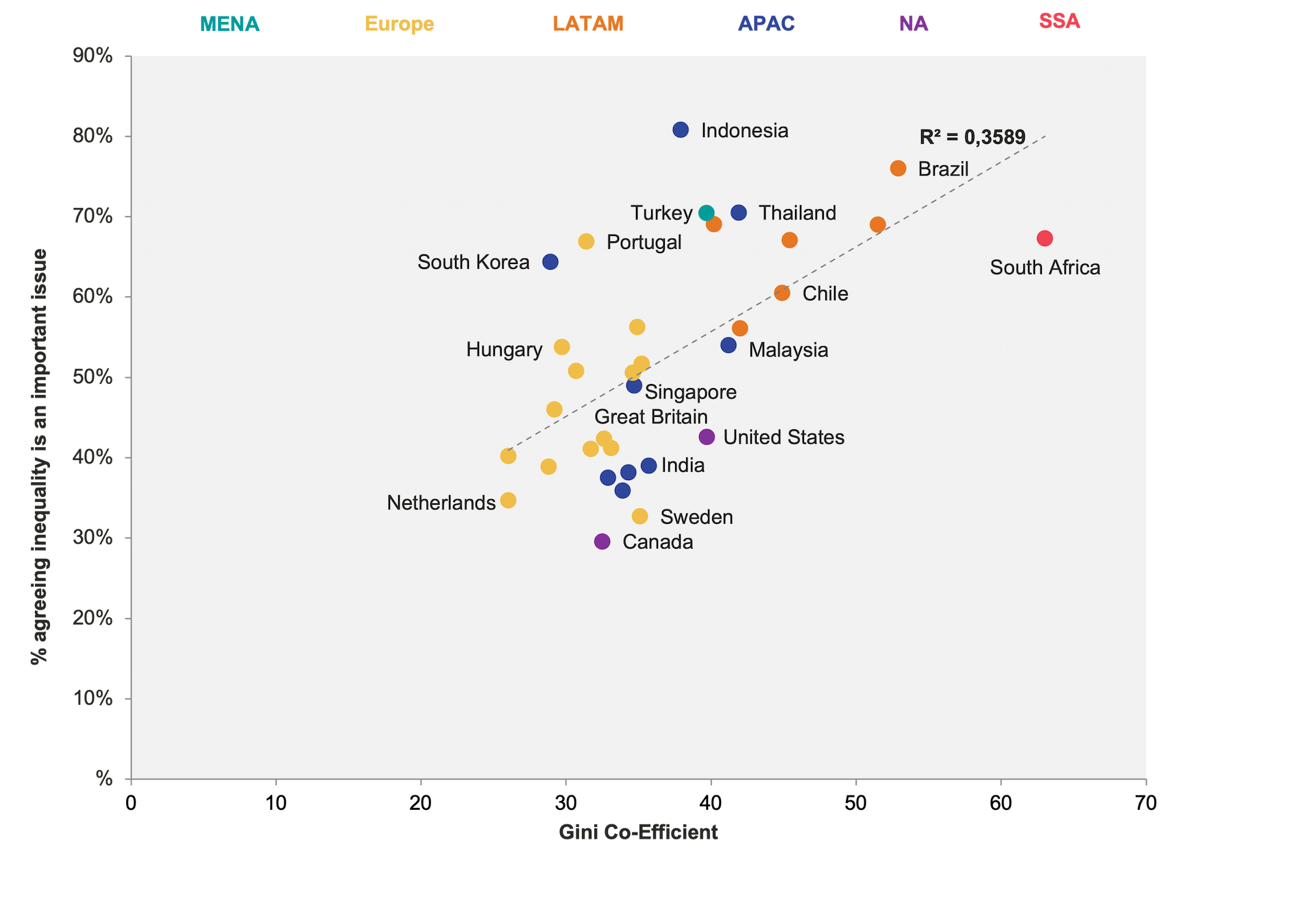

The extent to which citizens of a particular country are concerned about inequality there is related to how equally income is distributed there. We used the Gini co-efficient to test this relationship, as it is a useful proxy for other forms of inequality, which will often express themselves in terms of an individual’s income.

So, European and North American countries – which are less unequal – are also less concerned about it, whereas countries in Africa and Latin America are both more unequal and more concerned. Asia-Pacific provides an intriguing counterpoint, because even though the countries we studied are all within a relatively narrow band of actual inequality, there is a very wide spread of concern about it, with Australia, Japan, New Zealand and India all being relatively relaxed about the issue, and Indonesia, Thailand and South Korea all being more concerned than the average suggests they would be.

Pushback and progress

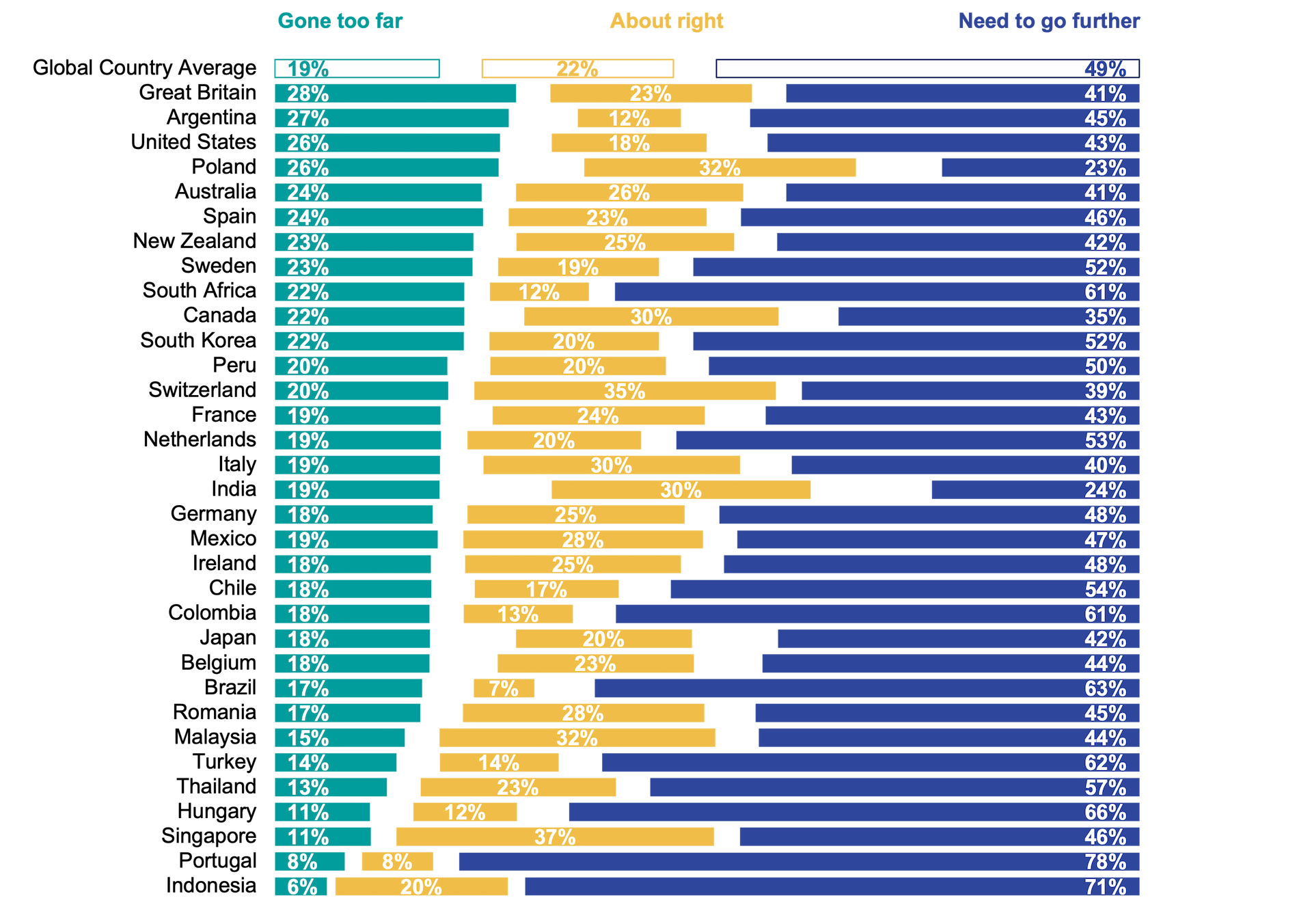

Countries which have done a lot to advance gender equality, LGBT+ rights, and reckon with historic racial injustice are also those where we discovered the most pronounced sense that this progress had now gone far enough. That said, in every case (except Poland) the overall balance of opinion was still in favour of doing more. Curiously, we did see that countries where English was the first language tended to be most likely to say that things had gone far enough, suggesting that these messages transmit very well across cultures that have something in common.

One of the strongest and clearest findings of all was that citizens around the world were universally of the view that government was primarily responsible for improving the situation in their country. Even though nearly half of global citizens believe that their success is the result of their individual efforts, this is not reflected in the view of who should take responsibility for making society fairer and more just.

Listen to the podcast

About this study

These are the results of a 33-country survey conducted by Ipsos on its Global Advisor online survey platform and, in India, on its IndiaBus platform, between February 17 and March 3, 2023. For this survey, Ipsos interviewed a total of 26,259 adults aged 18 years and older in India, 18-74 in Canada, South Africa, Turkey, and the United States, 20-74 in Thailand, 21-74 in Indonesia and Singapore, and 16-74 in all other countries.