What next for Rail? MPs' views on rail franchising

Recent calls by Labour backbenchers to bring train services back under public control are just the latest salvo in an ongoing political battle over the future of Britain’s rail network. Moreover, Ed Miliband’s response this weekend – while stopping short of a commitment to renationalisation – suggests that we can expect more frequent skirmishes on this issue in the build up to the 2015 general election.

Britain’s railways have long been a magnet for controversy. High speed rail, new rail infrastructure projects and long running concerns over capacity, connectivity and investment problems have never been far from the spotlight. Back in 2012, the collapse of the bidding process of the InterCity West Coast (ICWC) franchise made the front pages, with Virgin Trains and FirstGroup going head to head to convince the public that, despite issues with the way the process was handled by the Department for Transport (DfT), their business model offered the best deal for passengers and the public purse. Despite winning the contract initially, FirstGroup fell victim to irregularities in the selection process, and Virgin Trains was awarded a contract extension until 2017.

As the parties prepare their campaigns for what looks to be one of the most closely contested general elections for a generation, another facet of the industry and its structure has come under increasingly close scrutiny; that of passenger rail franchising and the argument over public versus private ownership of the nation’s railways.

Labour’s latest announcements follow the opening of bidding on the InterCity East Coast line franchise, which is being re-privatised after a brief period of public ownership. The route is currently operated by Directly Operated Railways; an arms-length holding company set up by the DfT following the default of National Express on its franchise contract in 2009. Too many this “renationalisation” has been a success; passenger numbers are up and both revenue and profits have increased during public ownership. As such, some transport commentators, as well as transport unions including the RMT, Aslef and TSSA, are questioning the motives behind the decision to return the route to private-sector operation, and the exclusion of Directly Operated Railways from the bidding process. Indeed, some see this move as ideologically motivated, arranged by the current Government to reinforce its narrative about the virtues of privatisation.

Ed Miliband’s comments appear to be an attempt to re-open debate on this topic and to carve out a distinguishing political stance ahead of the general election. Back in April 2014, building on the popularity of his promise to freeze energy prices for 20 months, the Labour leader hinted at the possibility of a shake-up of the current franchise model, should his party make a return to Government in 2015:

“We have got to look at these issues around the franchise. There are different models you can use. You can have a competitive model where there is a public option like there is in East Coast at the moment. So we are looking at different models for this.”

Ed Miliband, Guardian interview, 4 April 2014

These developments have served to raise the profile of privatised rail in the UK, with questions are being asked as to whether passengers and taxpayers are getting a raw deal. With annual fare increases a reliable source of passenger consternation, and commuters being singled out as a key demographic in marginal seats, the issue is only likely to gain momentum over the coming months.

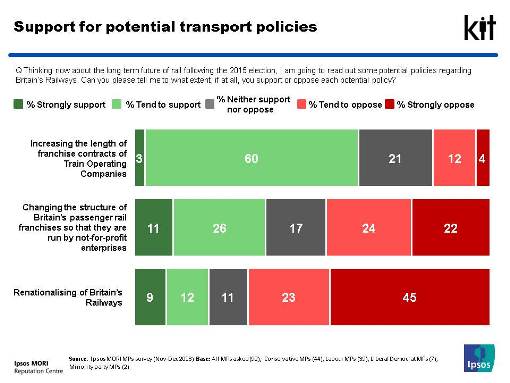

At the end of last year, we asked a representative cross-section of MPs to what extent they would support or oppose three specific potential rail policies following next year’s election. Judging by the balance of opinion, Ed Milliband has his work cut out if he is to achieve his goals and change the current model:

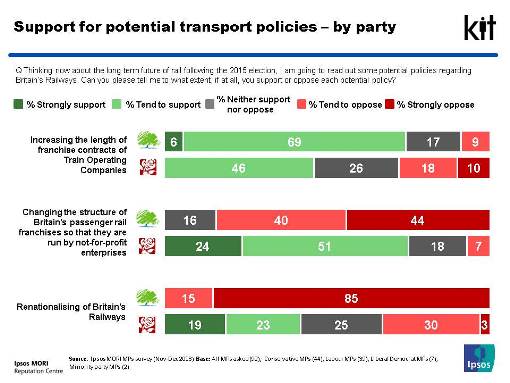

Firstly, the prospect of renationalising Britain’s Railways attracts few supporters overall; just one in five (21%) MPs would support the move, while over two in three (68%) oppose the idea. Support comes mainly from the Labour benches, where a large minority of two in five (42%) support the notion of renationalisation. Many of these MPs believe that standards would improve on a public-owned railway. This opinion is driven in part due to perceptions of poor management and prioritisation of shareholder profit over standards in the current status quo and, for others, due to the example set by the performance on the East Coast line:

“Purely on experience. The East Coast line (which I travel on a lot) is much improved and indeed transport is like energy, one of these issues whereby profit should be completely reinvested to make it better”

Labour Shadow Minister

However, Ed Miliband would need to convince a large minority of one in three (33%) Labour MPs that renationalising the rail network is a good idea. For many of these MPs, their opposition to renationalisation is down to the cost of doing so, alongside reservations on whether services would improve as a result. As one Labour MP put it:

“It would cost money to renationalise them and actually there isn't going to be that money around. If you spent the money on nationalising you haven't got money for investment. There is no evidence that it would be any more efficient”

Labour Backbencher

Perhaps unsurprisingly, all Conservative MPs interviewed were opposed to the idea. For many of these MPs, opposition is rooted in ideology (i.e. that the private sector would deliver better results). For others, the cost of such a move renders the idea unworkable, while for some, the memory of the days of British Rail is enough to dissuade them from supporting a move to renationalise.

“I remember what British Rail was like. A history of closure and if you look at my constituency, when I was born there were 14 stations in my constituency, and I was born under British Rail and there isn't one left. Do you remember British Rail sandwiches? They were a joke”

Conservative Minister

“I oppose the nationalisation of anything, I remember what British Rail was like, it was a shambles. Private sector companies are far better at running anything, particularly the railways”

Conservative Backbencher

So, with this in mind, an idea that may have a better a chance of getting through Parliament, should Labour win the election in 2015, is changing the structure of Britain’s passenger rail franchises so they are run by not-for-profit enterprises. Although more MPs oppose the idea (46%) than support it (37%), support is much more clear cut among Labour MPs; three in four (75%) would support such a policy. This suggests that this idea would gain more traction than wholesale renationalisation in the house should Labour win in May 2015. Again, as with nationalisation, not one of the Conservative MPs interviewed said they support this policy.

However, with support for both renationalisation and a not-for-profit model lying solely among the ranks of Labour MPs, it’s unlikely that any change will see easy passage through the House. Indeed, a reinforcement of the status quo may well be more likely. There is an appetite among many MPs to increase the length of franchise contracts for Train Operating Companies (TOCs). Overall, three in five (62%) MPs support this notion, while just one in six (16%) oppose extending contract lengths. Furthermore, support transcends the party divide. Although the idea might well include both private and not-for-profit franchises (we did not specify this either way when interviewing MPs), three in four Conservatives (74%) and just under half of Labour MPs (46%) said they would support the policy. Just one in ten (9%) Conservatives say they would oppose the move, while three in ten (29%) Labour MPs hold the same view.

So, for the time being, it’s probably safe to say that it is unlikely that the current private ownership model of Britain’s passenger rail services is going anywhere. However, with Labour keen to gain political advantage from rail policy and the increasingly high profile coverage of rail franchising, the situation could change after the election.

Ipsos’s MPs' survey runs twice annually, interviewing a representative sample of c.100 MPs from the UK House of Commons. Interviews are conducted face-to-face.