Opening Up the Economy Might Mean Less Personal Privacy. Do Americans Want in?

What you need to know:

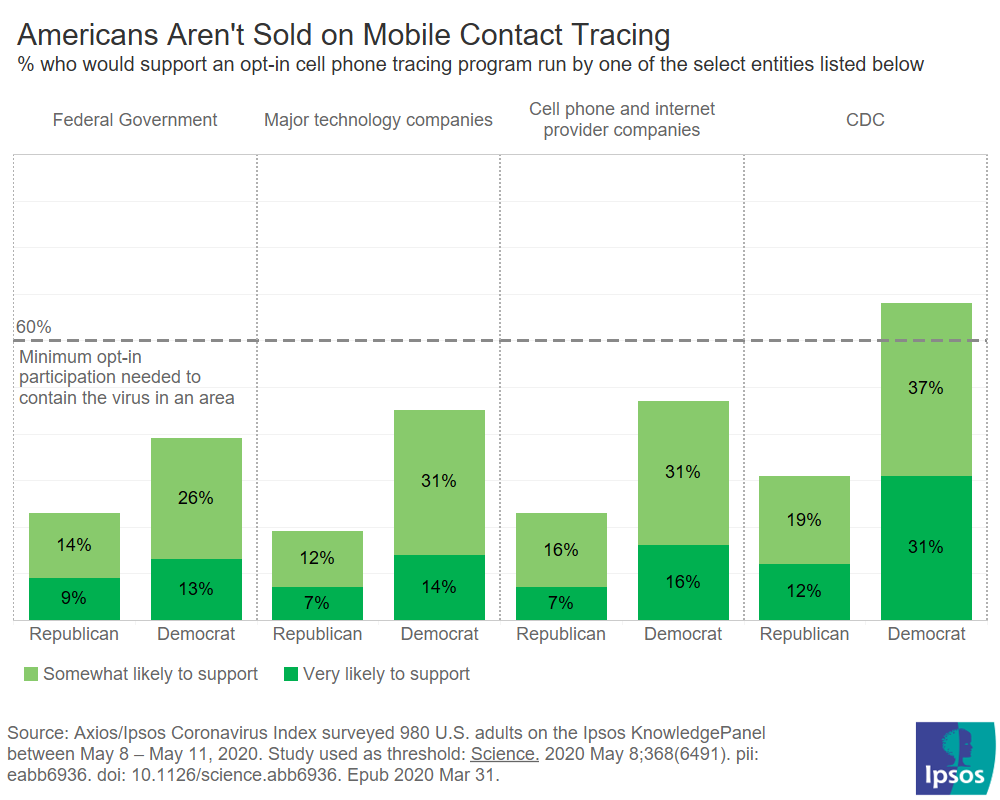

- Most Americans don't support mobile contact tracing.

- That support moves based on who runs the mobile contact tracing program, with the CDC and public health officials winning the most support overall.

- Approval of mobile tracing programs cleaves along partisan lines.

In front of Congress yesterday, Dr. Anthony Fauci told a virtual room of senators that “little spikes could turn into major outbreaks” if states and localities move too quickly to open.

Nearly two months ago life around the U.S. came grinding to an abrupt halt as coronavirus cases began soaring. Now, many Americans are itching to restart public life and wondering when and how that might happen.

To lift stay-at-home orders safely, experts agree that governments need some way of tracking and tracing potentially infected individuals and testing them. Though the most advanced method, using cellphone data, isn’t winning any decisive majorities among the public.

Most Americans are unconvinced about the benefits of cellphone tracing, recent Reuters/Ipsos polling finds. Less than half (41%) of U.S. adults report that they would participate in mobile device tracking to help fight COVID-19. There was a 12-point divide between Democrats and Republicans on this question, with half of Democrats backing a location tracking program and 38% of Republicans supporting it.

Notably, when this was asked three weeks ago, a government mandate to participate in location tracking didn’t move the numbers all that much. When respondents were asked if they would support a government mandated mobile tracing program, roughly 40% supported it and 46% opposed it. In fact, the partisan divide practically disappears. 45% of Democrats back a government ordered tracking program compared to 43% of Republicans.

While many Americans are generally skeptical about mobile tracing, what entity leads a program like this swings support significantly, the Axios/Ipsos Coronavirus Index finds. 51% of Americans agree that they would be very or somewhat likely to opt-in to a cell phone-based contact tracing program run by the CDC and public health officials.

On the other hand, only a minority (31%) of Americans would be very or somewhat likely to opt-in to a cell phone tracking program run by the federal government, 20-points behind the CDC. Major technology companies (32%) and cell phone or internet providers (35%) win only a fraction of Americans over. No hypothetical program gets any significant share of strong support.

To be effective, a recent study by epidemiologists at Oxford estimate that at least 60% of people in a given area would need to be part of a mobile tracing effort to contain the virus, heightening the importance of public support and trust in such an initiative.

Partisanship plays a major role in how that support moves. Digging deeper, 68% of Democrats would be willing to engage in a CDC-run digital tracing project compared to 32% of Republicans, a 36-point gap.

Skepticism of the federal government seems to narrow that partisan divide. While winning the lowest level of support overall, there is only a 16-point difference between Democrats and Republicans when it comes to opting into a cellphone monitoring initiative run by the federal government. Notably, no majority of Democrats or Republicans support such a measure.

In reality, the management of such a program wouldn’t fall to just a single entity. Among the 25 countries that are beginning to make mobile contact tracing apps, many rely on a vast network of developers pulled from the private sector, according to MIT Technology Review's tracking. Google and Apple began releasing APIs so that health agencies and developers could begin working on mobile tracing apps at the beginning of this month.

However, Americans trust in internet companies and the government was on shaky ground even before the pandemic. A CIGI/Ipsos study from last June found that half of North Americans disclosed less personal information online due to their distrust in the internet. Only 48% believe the government does enough to safeguard their online data and personal information.

In countries already implementing opt-in mobile contact tracing use is limited. Singapore rolled out a mobile tracing app in March, and one month later only 12% of people reportedly use it. Now facing a second wave, the consequences of the public not fully buying into a program are clear.

Even with manual contact tracing, the margin of error is unforgiving. The Oxford epidemiologists who estimated the percent of people who need to participate in mobile tracing also projected that missing a day of contact tracing was the difference between opening safely and shutting down again. Little spikes can turn into major outbreaks quickly.

It is unclear whether the public will be able to overlook the low levels of trust that have come to characterize the relationship between tech companies, the government, and the public. How we move on from here might depend on just that.