Where women are nine months into the pandemic

As the country rounds the bend on the ninth month of living with COVID-19, the pandemic economy is deepening the existing inequities in the labor market, particularly for women and, more acutely, women of color.

There are two reasons for the uneven impact the COVID economy has had on women: the first is that the pandemic has impacted sectors that skew more female in their workforce, like the retail, restaurant, and hospitality industries; and the second is that women often have to take on more childcare responsibilities in remote learning situations.

The latest figures from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that the unemployment rate for women across races seems to be evening out or even lower than the unemployment rate for men, an improvement from the spring. But, this development comes at the expense of women leaving the labor force and therefore do not count as unemployed. As of October of this year, there were 2.2 million fewer women in the labor force than in February. Hispanic and Black women are leaving at higher rates than white women.

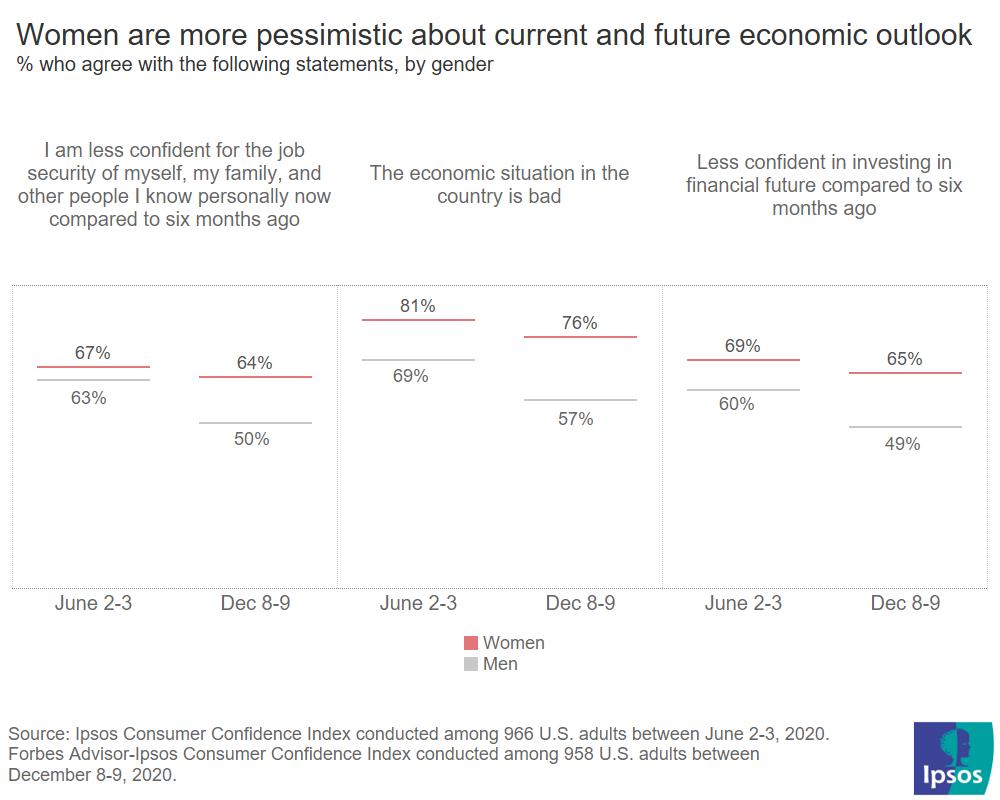

Notably, those hurt most by the economy are taking notice of the disparate and sluggish pace of aid and recovery. Women view the current economic situation much more pessimistically than men. Three in four (76%) women believe the economic situation of the country is bad, 19 points ahead of men.

Consequently, women remain much less confident in their ability to invest in their future by doing things like saving for retirement, which holds long term implications for their future financial health.

And, while women have remained about as confident in the job security of their inner circle over the past six months, men grew more certain over that same time. That feeling of job security is not the same for all women either. Black and Hispanic women feel much less secure in their jobs right now than white women. Half of Black women (51%) and 62% of Hispanic women are concerned about their job security, while only 37% of white women are, according to the Axios/Ipsos Coronavirus Index.

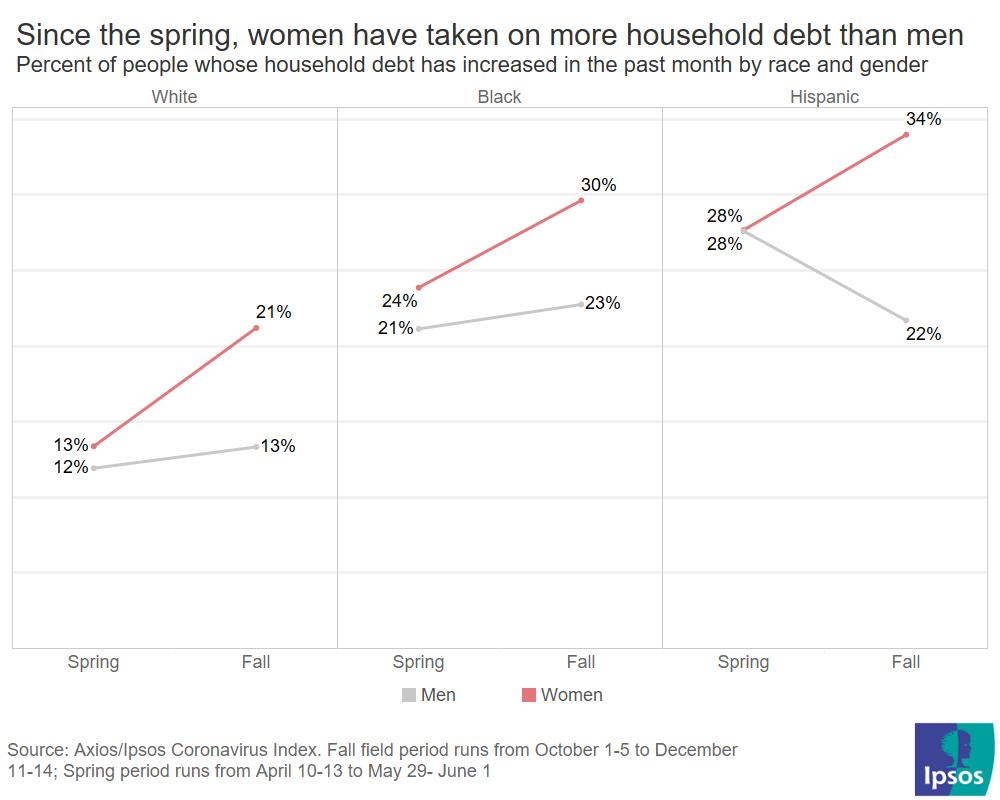

Given the financial uncertainty hanging over women’s heads, more women are taking on household debt. Back in the spring, there was little to no difference in how women and men increased their household debt. But now, a sizeable gap is opening between men and women on this question, one that will be a hard problem to shake given the compounding problems of job insecurity and childcare.

Childcare responsibilities are drawing women out of the workforce in droves. Most parents with school-age children reported sending their kids back to school virtually, putting a resource crunch on families. As many schools across the country continue to engage in hybrid or remote learning, mothers are still often the ones who take care of childcare in the home. Women are twice as likely as men to say they will mostly handle childcare themselves, and men are nearly four times more likely than women to tell researchers that their partner or spouse will take care of most of the childcare tasks.

The financial burden of raising children is weighing on families. One in three Black households with school-age children reported that their ability to afford household goods got worse in the past few weeks. For Hispanic families one in four are in a similar situation, while one in five (19%) white families are facing the same concerns.

On a more macro scale, the flight of women from the workforce holds severe implications for any economic recovery now and in a post-COVID future. In total, the price tag for women leaving the workforce at roughly this rate is $64.5 billion in lost wages and economic activity.

When long-term unemployment or a time away from the working world interacts with gender and race, it worsens pre-existing problems within the labor market. It reduces the pipeline of talent getting trained and then promoted to management roles; it diminishes the productivity of the economy at large; and, the longer women stay out of work, the more money gets shaved off from their lifetime earnings. That means fewer women of color in management roles, lower lifetime earnings for women, and an economy that will not grow to its full potential.

At the most basic level, women are struggling. Without the private and public sector reengaging women who are unemployed or not in the labor force, the inequities that are deepening in the present moment will not go anywhere, even when the pandemic is over.