Keeping the patient at the heart of care

The Health and Social Care Committee’s inquiry, Integrated care: organisations, partnerships and systems, recently published its report. Our four organisations gave evidence, in which we highlighted the patient’s perspective of a complex and disjointed health and social care system. We are very pleased that our thinking seems to have shaped the Committee’s conclusions and welcome its placement of the patient at the centre of integrated care. It recognises that organisational and structural reform is simply a means to an end:

It is absolutely essential not to lose sight of the patient and their families in any debate about NHS and care reform. Organisational and structural changes are merely a means to an end: the litmus test to determine whether these reforms succeed will depend on how effectively these new structures and organisations deliver better integrated care at the patient level.

The end goal is a more joined up service with patients at the centre, focused on what matters to them. And the Committee’s report reflects that, emphasising that the measurement of its success should be defined from the patient’s perspective. The report urges the Department of Health and Social Care, NHS England and NHS Improvement to

clearly define the outcomes the current moves towards integrated care are seeking to achieve for patients, from the patient’s perspective, and the criteria they will use to measure whether those objectives have been achieved.

Let’s take a hypothetical patient, Linda. There are thousands of Lindas across the country. She has arthritis and recently had a minor stroke. She cares for her husband, John, who is living with dementia. Linda needs to see a GP as the pain in her hands from the arthritis has increased sharply and she’s finding day-to-day tasks difficult. She has booked the appointment short notice and is not able to see her own GP, so she sees someone she doesn’t know. Linda has a rare form of arthritis that the GP is not aware of, so she explains what it is, how it affects her, and what treatment she is on. The GP is interested to hear about the treatment and checks the BNF for what extra painkillers would be best for Linda, given the medication she is on following her stroke.

Two weeks later, Linda has a regular appointment with her arthritis consultant. The consultant asks how she has been and Linda says the additional painkillers have been working well for her. The consultant asks what additional painkillers. Linda points to the computer screen and references her recent GP appointment. The consultant explains that she does not have access to those details – that the hospital’s records are entirely separate from the GP’s. Linda did not know this, but now she does know she is not surprised. It explains why neither ever seems to have the full picture of what’s happening to her. She tells the consultant why she went to see the GP and what the outcome was. Then she explains that she is finding looking after herself difficult at the moment, and the consultant suggests she talk to her GP.

Linda books an appointment for two weeks’ time so she can see ‘her’ GP. Linda has been seeing him for 30 years now and they have a good relationship. They exchange pleasantries. Then the GP asks how Linda has been. Linda says it is difficult for her to do things around the home and she needs some help. The GP sympathises and says he will put her in touch with social services to hopefully organise some help, if she meets the needs threshold. Linda comments that it is great the practice offers this service, and the GP explains that it is a local authority service, not NHS. Linda doesn’t quite understand what this means, but she nods. She says that she’s feeling lonely because it’s more and more difficult for her to get out, between her conditions and John’s dementia. The GP sympathises again and says there is a charity he can put her in touch with who can help with this. Linda nods again and leaves, thanking the GP for his time.

A few days later, Linda visits the GP practice again with John, who has had a fall and needs checking. As an emergency appointment, Linda and John see another GP they only see from time to time. Linda explains John’s background – the average dementia patient has to explain their story 20 times – and that she is finding it increasingly difficult to look after him. The GP checks John’s physical health and says that he will speak to Linda and John’s GP about organising a multidisciplinary team meeting to talk about their situation. Linda blinks. Then she nods. Well surely that must be a good thing? Great, thank you ever so much doctor. And she leaves.

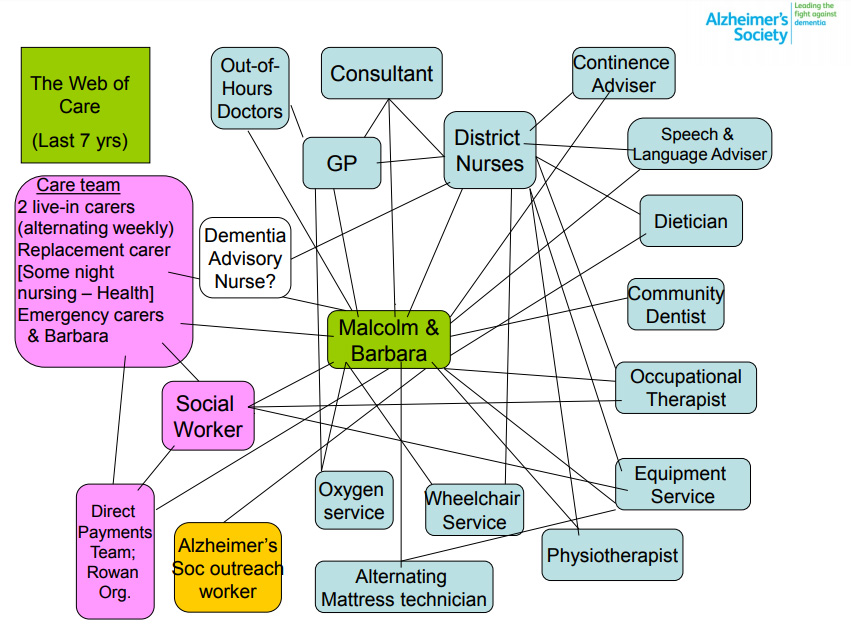

No-one thinks this is the best care that can be provided for Linda and John – not Linda, not her healthcare professionals and not policymakers. The following diagram, developed for National Voices and the Alzheimer’s Society by Barbara Pointon, shows the ‘web of care’ for someone living with dementia. Barbara, as the carer, had the full time job of coordinating Malcolm’s care and contacts with the system overloading her and taking her away from direct caring. What people want from ‘integration’ is for care to be properly coordinated so that things work properly and the burden of treatment is reduced.

But it is so difficult when working through the myriad of legislative and other issues to remember these types of patient stories. Regardless of the many challenges the Health and Social Care Committee’s report outlines for implementing integrated care, we must remain focused on what matters to the patient so that the Lindas and Johns of the world get the care they need and deserve. This is the end goal to which we should all aspire.

- This article was written in conjunction with National Voices, the Richmond Group of Charities and Healthwatch