Political Behaviour Part 1: Turnout

As the UK General Election draws ever closer we thought we’d look at what the behavioural literature suggests about important aspects of political, or more specifically voting, behaviour. In this, the first of three posts over the next week, we consider voter turnout, why it is we vote and some of the key influences on our turnout behaviour.

As the UK General Election draws ever closer we thought we’d look at what the behavioural literature suggests about important aspects of political, or more specifically voting, behaviour. In this, the first of three posts over the next week, we consider voter turnout, why it is we vote and some of the key influences on our turnout behaviour.

Why do we vote?

It remains a good question. As Downs’ paradox suggested back in fifties, the reward derived by the individual from voting may often outweighed by the costs and the smaller the reward the less likely one is to turn out. A more recent model looks at things slightly differently. Harder and Krosnick see an individual’s turnout behaviour as a function of three things – motivation to vote, ability to vote and the difficulty associated with the act of voting:

Likelihood of voting = (Motivation to vote × Ability to vote) / Difficulty of voting.

This is a recognisably social psychological – even Lewinian -conception of voting behaviour. Interestingly, it also proxies one of the most helpful behavioural models around – COM-B - that understands behaviour as the product of interaction between capability, opportunity and motivation. Whether you like Downs, Harder or find it more convincing to understand voting as dynamic self-expression, when we ask people in focus groups about their voting behaviour typical responses involve some variant of “I’ve always voted XYZ because my parents/family always did.” This is not to say that children simply vote as their parents do but this kind of comment is instructive in the sense that it’s consistent with literature indicating the importance of habit, social influence and identity on turnout.

While some of us are election-specific voters, responding to particular candidates or issues, many of us are habitual voters who consistently turn out in every election. What’s more, the very act of voting may be habit forming - once someone has voted they’re more likely to vote again. Two likely explanations for this are, first, that voting makes one more likely to identify as a voter, and, second, that once one has voted future voting is less costly in that there is less uncertainty or, perhaps, perceived hassle involved (ie knowing voting procedure, location of the polling station etc).The latter mechanism may be particularly helpful in explaining habitual voting, making the case for the importance of incorporating ‘difficulty’ in any voting behaviour model. Perhaps a better understanding of difficulty might even help engage some of the estimated 7.5 million unregistered voters in the UK.

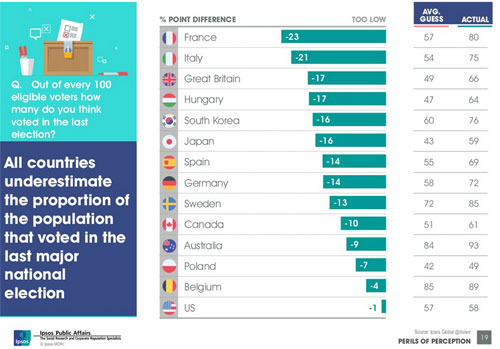

Plenty of attention – at least in the US - has rightly been paid to using descriptive norms to influence turnout behaviour, such as using messages emphasizing high expected turnout to motivate moderate and infrequent voters. Of course, this kind of intervention is also particularly worthwhile in the UK context where we substantially underestimate the proportion of the voting population. Although as our Perils of Perception work suggests, we’re hardly unusual in this regard.

However, as our typical focus group responses imply, it is likely that subjective norms – perceived social pressure – as well as group identity also have a role to play in understanding turnout.

It’s intuitive that voting is a very social behaviour influenced by our interactions with our various social networks. Indeed, evidence suggests that voting is actually highly contagious and that propensity to vote may be passed between household members who become more similar over time. Another socially related influence on our turnout behaviour – and likely our vote choice – is ‘social image’ or voting because others might ask us whether we have and we don’t want to be embarrassed or forced to lie.

Beyond the household and immediate social ties, whether and how we vote may be influenced by who are neighbours are, and the extent to which we interact with them, or whether and how strongly we identify with a particular social group

A stark and fascinating example of how group identity might affect turnout as well as choice of candidate may be seen in the 2008 US Presidential Primary in Los Angeles. Los Angeles is “hyper-segregated” residentially with tension between the Latino and Black community a “social reality in some neighbourhoods.” The so called “group threat hypothesis” suggests that members of one group are politically motivated by the presence of another group. Work by Ryan Enos found that Latinos were less likely to vote for Obama as their proximity to Black communities increased – evidence consistent with the idea of group threat here specifically played out in the context of ethnic groups.

Clearly there are many interacting influences on turnout and candidate choice and many are environmental, that is, outside the individual. And just in case you were still in any doubt about the importance of social influence it seems even the Ipsos Worm may be affected, with the worm itself a form of influence on our perceptions of who wins televised debates.