What happens on Twitter doesn't stay on Twitter

Earlier this month, when the president was asked at a press conference about the White House’s response to the coronavirus, he told a reporter to ask China that question and then abruptly walked off stage.

That moment encompasses what is shaping up to be a key part of the president’s reelection playbook: blame China and move on.

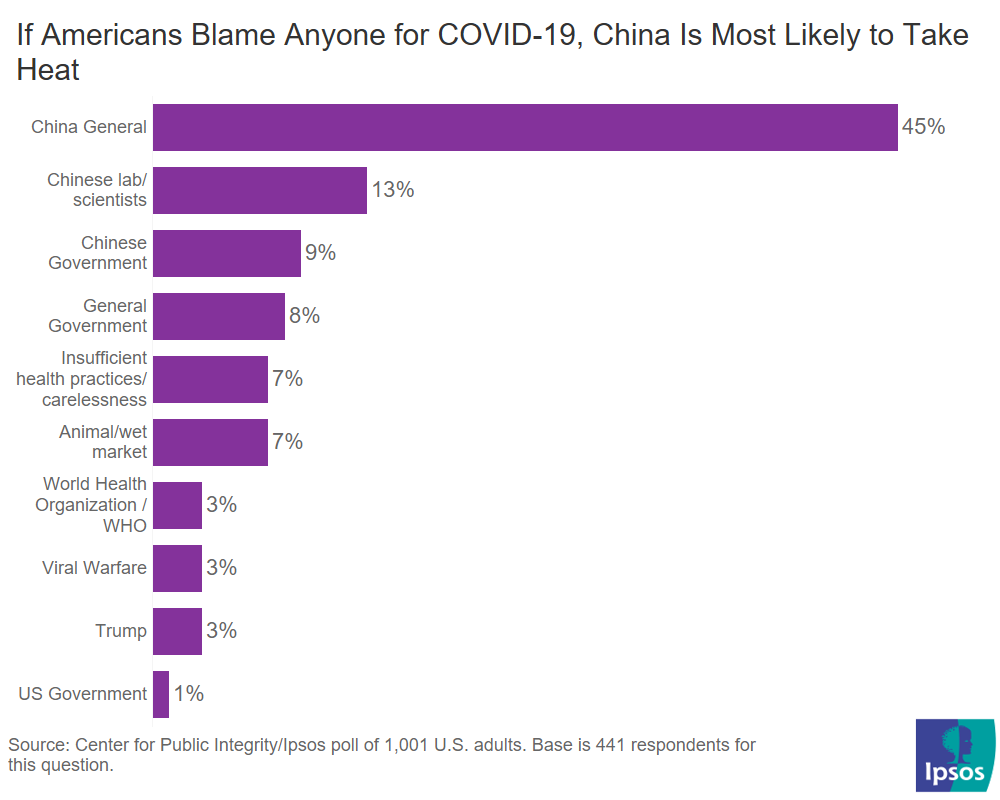

Parts of the public are absorbing that messaging. While most Americans (56%) see the coronavirus pandemic as a natural disaster, a plurality (44%) blame specific people or organizations for the crisis, with China taking the most heat among that group, a recent Center for Public Integrity poll conducted by Ipsos finds. Among the people who blame a group or organization for the pandemic, two-thirds blame China or Chinese people specifically.

In fact, three in five (60%) Asians have witnessed someone blaming Asian people for the coronavirus pandemic. Hispanic (48%) and African Americans (43%) are much more likely than White (27%) respondents to report witnessing someone blaming Asian people for the of the virus.

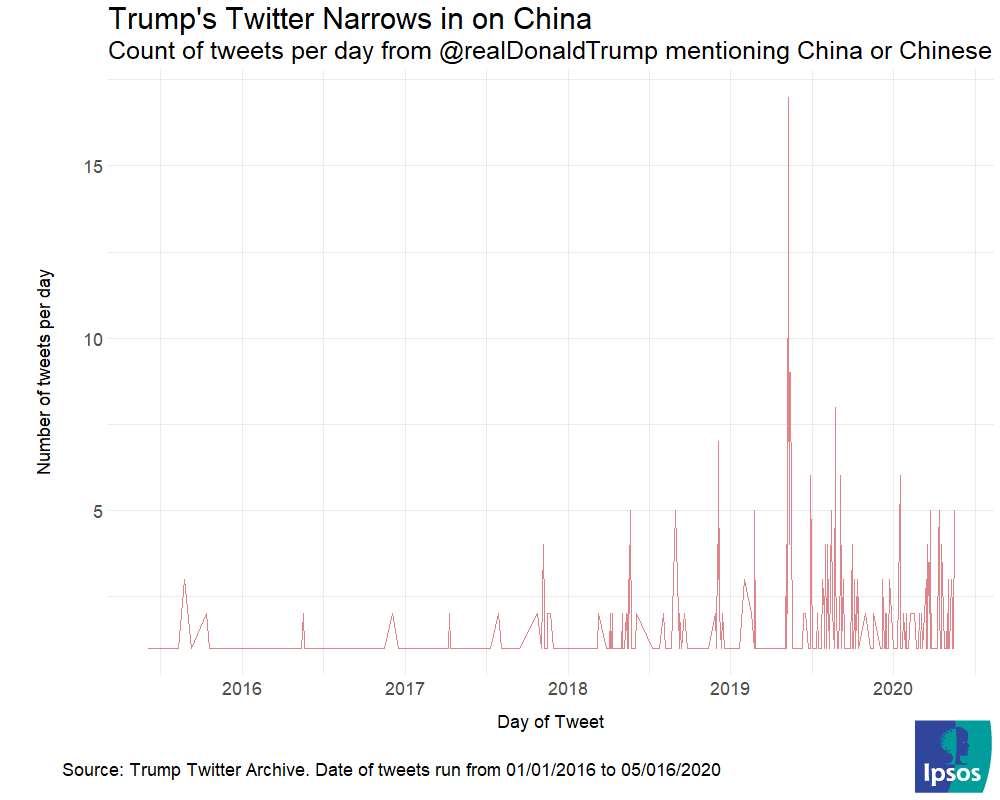

President Trump’s twitter feed shows this political play in action. Trump has upped his daily mentions of China in 2020 coming off a particularly volatile year where the president pushed one of his major campaign points through the social media platform, tweets pulled from the Trump Twitter Archive finds.

Right now, President Trump tweets about China nearly every day, if not multiple times per day.

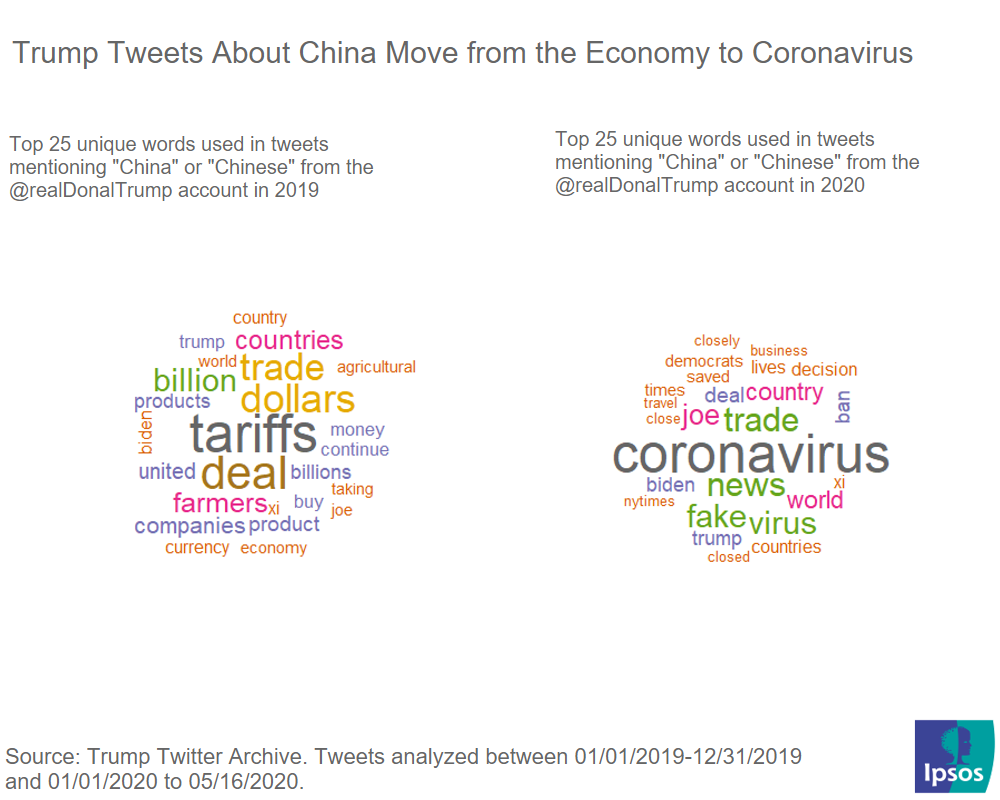

Twitter for the president is a way of underlining his thoughts, pushing a news cycle along, and/or attacking his political enemies. This is evident in how Trump’s tweets about China are framed. So far this year, all of Trump’s tweets that mention China focus on the coronavirus with fake, news and virus other notable top words.

Joe Biden – Trump’s rival in the 2020 election – is also called out more frequently in connection with China this year than last. Heading into the election, Republicans have settled on dubbing Democrats as “soft on China”, a strategy Team Trump had in mind even before the coronavirus began to ravage the nation.

This isn’t the first time the president has sparred with China via Twitter. Previously, the president’s account came into play often during the U.S.-China trade war. In 2019, the President – in one single, heated day – tweeted about the country 17 times. Major diplomatic escalations—like a hike in tariffs—was discussed and announced over the social media platform.

As unpredictable and erratic as those tweets may have been, they had a very real and tangible effect on public opinion.

During this time, Pew Research Center found that perceptions of China under President Trump’s presidency have soured among Americans, particularly in the past two years. In 2018, 47% of Americans had an unfavorable opinion of China. By 2019, that number moved to 60%, coinciding with the President frequently duking out and airing his diplomatic grievances in 140-characters or less.

Twitter is not a new tool for the president. Immigration was one of his signature issues for much of his presidency. Accordingly, his Twitter account was rife with mentions of immigration, with more than 1,100 Tweets on the topic between him taking office and 2019, according to a New York Times analysis.

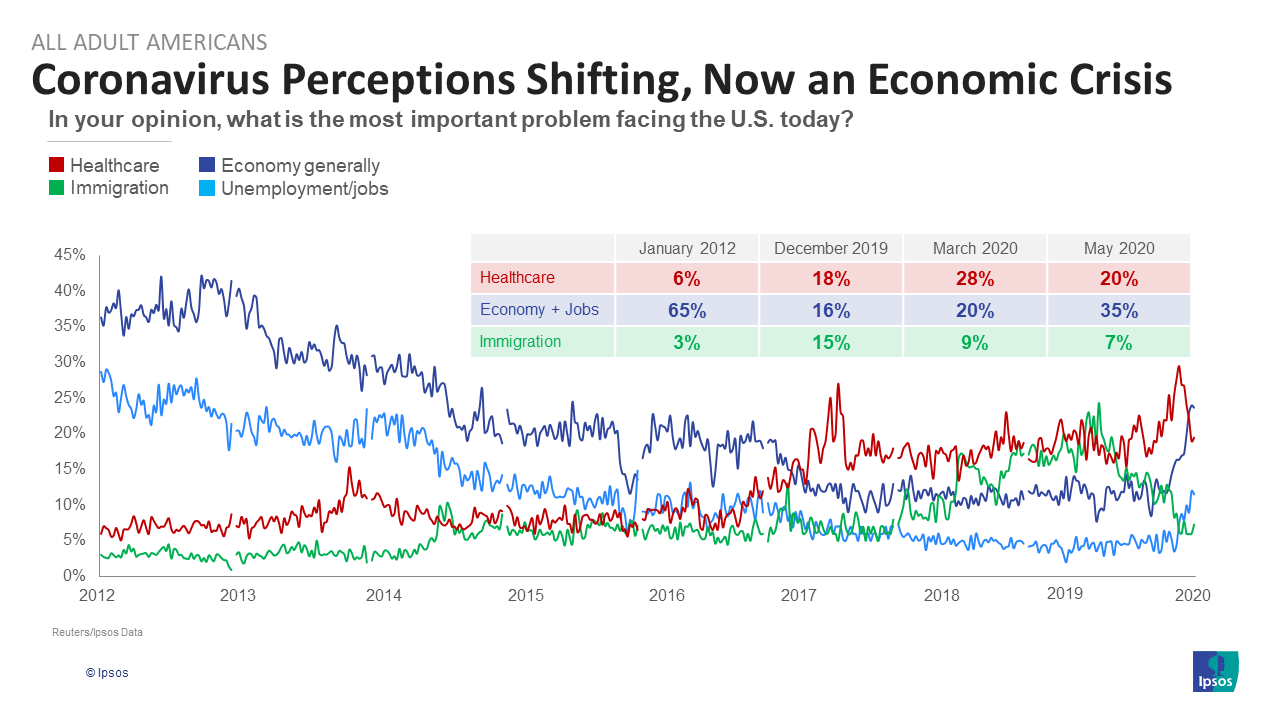

During the pandemic, the political calculus has changed. Immigration is no longer on the front burner, even for his base, supplanted by concerns about employment, jobs and healthcare. Trump is shifting gears accordingly, mentioning immigrants or immigration only once this month.

Where immigrants and immigration were reliable scapegoats before, China is now playing that role during the pandemic. While there are questions about what China could have done at the virus’ onset and the speed and truthfulness of their initial reporting, that nuance is not being conveyed by the president. With more than 38 million Americans out of work, economic success cannot be the pillar of Trump’s reelection campaign. Instead, he has pivoted to blaming China wholesale for the United States’ current crisis.

But, political moves and messaging from the president don’t live and die on Twitter.

In the first month of the nationwide lockdown the Asian American Pacific Planning Council, a non-profit, logged nearly 1,500 self-reported instances of physical or verbal attacks against Asian people. A startling finding given much of the country was confined to their homes under shelter-in-place orders. Anecdotes and studies of online chatrooms, like 4chan, report similar upticks in the use of Asian slurs and harassment percolating on these forums. In March, the FBI circulated a letter to local law enforcement across the country warning of a potential surge in hate crimes targeting Asian Americans.

Analysis of FBI data found that since the last presidential election, counties Trump won by a larger-margins were associated with more hate crimes. Hate crimes, which usually peak in the summer, hit a highwater mark between October and December in 2016, the heat of the presidential election, and continued at that level throughout 2017.

Political messaging during an election year is guaranteed to be brutal. A pandemic, history-making economic fallout, and reckless tweeting from the president is taking it to a dangerous level. Whether Trump is fanning (or simply trying to capitalize on) the flames of anti-China sentiment, the side effects are very real for millions of Americans as the nation continues to struggle with how to move on from here.