Financial Strategies for Later Life

In recent years, we have witnessed a succession of disruptive events: a pandemic, an inflation shock, extreme weather, geopolitical tensions and the rise of Generative AI. These changes are dramatic, widespread and enduring, requiring businesses and governments to adapt. Yet gradual changes that are subtly reshaping our socio-economic fabric, notably a rapidly ageing population, escape our immediate notice.

The media obsess about ‘Millennials’ or ‘Gen Z’ as disruptors, but in fact ageing (which will affect every generation) is having even larger effects. Rising life expectancy and falling birth rates mean populations around the world are getting older. In the UK, 'Perennials' are not only growing in number but also in economic influence, holding a significant portion of the nation’s wealth. However, ageing is portrayed as a ’narrative of decline’, not a time of opportunity and change.

People in their later years are increasingly packing their life to the full. For many, their reality doesn’t necessarily align with the labels they’ve been given. They’re not wilting in the autumnal years of their life. They’re perennials. Like their namesake in nature, they are hardy, with the ability to withstand changes to their environment; they adapt, evolve, and grow anew.

Key takeaways

- 'Perennials' are not homogenous; financial service providers need to consider more granular, life-stage based segmentations to develop targeted products.

- With many Perennials feeling unprepared for financial demands post-retirement, there is an opportunity for financial advisors to provide affordable, personalised, and accessible financial planning.

- Expand educational resources to cover 'whole retirement' planning and digital literacy to assist older adults in navigating complex financial decisions.

- Consider cross-sector solutions like platforms that coordinate healthcare payments, insurance claims, and financial advice, recognising the growing intersection of financial planning and healthcare needs.

- Financial services should move beyond the traditional stereotypes of older adults as frail or cautious, addressing the diverse realities and potentials of Perennials' financial lives.

As a collective, Perennials are the happiest generation. However, the recurrent financial volatility of recent decades, paired with the tipping points that come with ageing, highlights that financial planning and management in later life are as unique as individual life experiences.

As a collective, Perennials are the happiest generation. However, the recurrent financial volatility of recent decades, paired with the tipping points that come with ageing, highlights that financial planning and management in later life are as unique as individual life experiences.

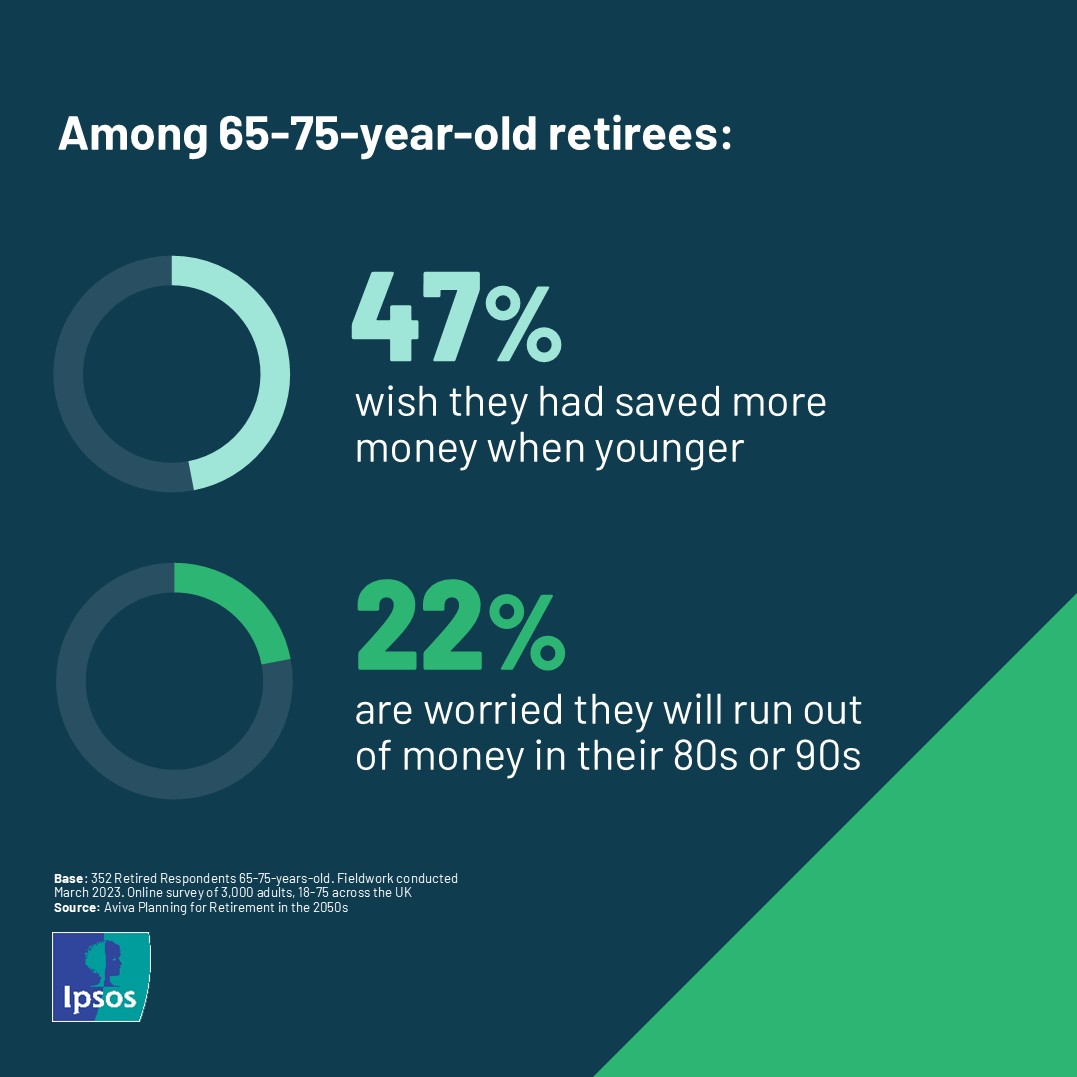

While Perennials hold more wealth than younger generations, this wealth is notably concentrated among those nearing retirement or those who own their homes outright. Between 2018-2022 the 65–74-year-old cohort have seen an increase of £3,400 in real terms. Yet, our recent study for Aviva also reveals that some new retirees within a similar age group of 65-75 feel unprepared for the evolving financial demands of later life, which undermines the opportunities of this group.

This lack of preparedness is likely due to the significant gap between expected income and the fluctuating cost of living, one exacerbated by stagnant wages, increased taxes, and rising housing and healthcare costs. Indeed, it is important to acknowledge that poverty and financial insecurity exist among older individuals, with 2.1 million people aged over 65 years old living in relative poverty in the UK today: that is almost one in five people (18%) in this age group1.

Retirement income

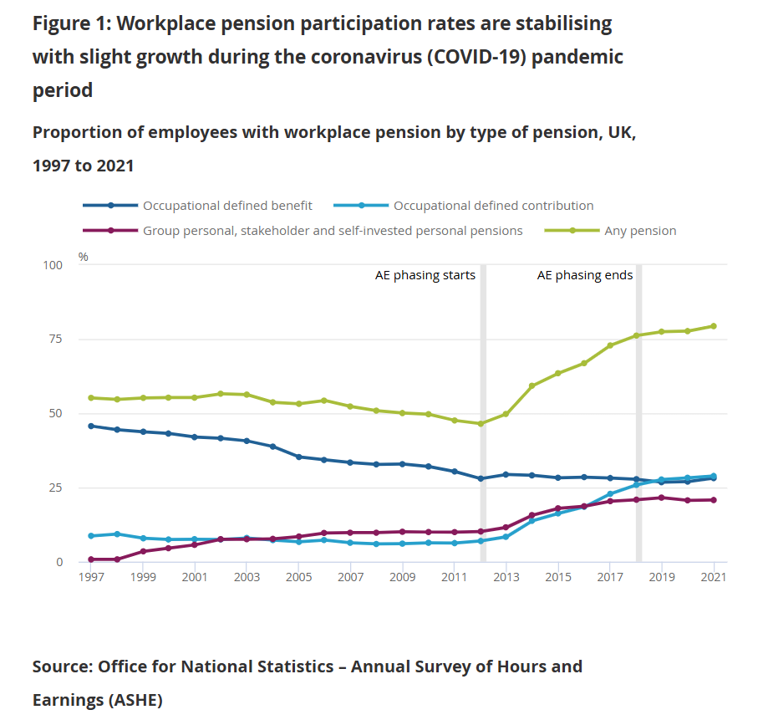

A diversity of retirement income sources reflects the mix of options that today's older adults experienced earlier in life, whether actively chosen or passively received. Within the ‘close to retirement’ cohort, many individuals are heavily reliant on the final outcomes of defined contribution pension schemes, with varying portfolio sizes, fees and charges, investment risk profiles and market fluctuation exposure. In contrast, many current retirees have received generous defined benefit schemes, high-interest annuities, and a triple lock on state pensions all in parallel to an increase in value of housing assets.

This raises a question: in a world where life expectancy continues to lengthen, have those currently aged 65-74 years old saved enough to comfortably manage the heightened costs of the very latest stages of their life?

Understanding these diverse experiences is key to comprehending the strategies that Perennials adopt in their financial journeys. These pressures, combined with global economic unpredictability, demand innovative, flexible solutions that prioritise individual circumstances and protect against economic uncertainties.

As such, there is an urgent need to rethink traditional life-stage models and financial products to align with these evolving and diverse needs. It is crucial to challenge the prevailing stereotypes and examine the unique life experiences against the myths we hold about Perennials.

Let’s explore these myths…

All Perennials are cautious

The reality of 'old age' is changing. Life expectancy in the UK averages around 82 years2 and is projected to extend further still although perhaps at a slower rate. For many, formal retirement is no longer a singular event but a gradual process and psychologically the ideal retirement age increases with age. Improved health, increased life expectancy, and greater digital accessibility encourage many to delay retirement or seek new job opportunities. Today's youngest adults, aged 18-24, consider 58 as the ideal retirement age whereas older adults between 65-75 years old, envision retiring at a later age of 713. Among the pre-retired, 52% of those aged 65-75 years old are ‘postponing’ retirement, 20% continue working while drawing a pension and 19% have yet to consider retirement options, believing it is too soon to plan4.

Further Ipsos data suggests that many Perennials express concern about the future, particularly regarding the strength of the global economy and potential tax increases in the UK, in contrast to the more optimistic views of the younger generations5. But within this general pessimistic outlook, attitudes towards risk would seem to be strongly related to actual age: the very oldest individuals being the most risk averse.

All Perennials are frail

The physiological process of ageing differs for everyone. It influences access to healthcare, housing, technology, travel, and one’s social life. Many Perennials remain active and relatively healthy throughout their lives, as reflected in our findings from the 'Life in the UK' report. Those over 55 years old generally experience heightened levels of wellbeing across all social, economic and environmental dimensions relative to younger age groups.

Of course, underneath these headlines, the picture is much more nuanced: differing experiences reflect the non-linear and sometimes unpredictable nature of one’s life journey. Groups such as those with disabilities, reduced mobility, health concerns, and living in social housing or deprived areas are more likely to encounter lower wellbeing levels. Ipsos data, drawing upon FCA’s vulnerability framework, highlights a significant increase in health-related challenges and access issues after the age of 80, which directly increases an individual’s expenditure on healthcare6.

Housing needs, either real or perceived, also evolve. Nearly a quarter (23%) of all those aged 50 and over have relocated within the past five years. Of these movers, over one-third (37%) aimed to lower their living expenses, whilst more than a quarter (27%) had sought to release equity from their previous home7.

All Perennials are well off

As discussed previously, the over 65s are holding an even greater share of the UK national wealth. Median wealth peaks between ages 55-64 when individuals are typically employed and contributing to retirement savings. However, while the 65-74 age group remains among the wealthiest, median wealth notably declines post-75.

This reflects the typical U-shaped spending trajectory of Perennials: active expenditure in early retirement, low spending in 'slow-go' years, and increased spending in late life due to healthcare costs. Until recently low interest rates have made annuities less attractive, and the long-term benefits of pension freedoms remain uncertain, creating vulnerabilities in uncertain economic conditions, especially among those with high healthcare needs or in the 'sandwich generation' caring for both children and aged parents.

Despite misconceptions about affluence, there's a complex interplay between saving and spending that defines the financial mindset among Perennials. Many, particularly the newly retired, possess ample financial resources and have a significant spending power. Yet they also face psychological barriers associated with a fear of depleting savings, despite having a stable income.

Our Financial Research Survey data reveals a marked change in the saving patterns of individuals after 60 years of age. Earlier in life, savings are allocated for specific purposes, including emergency funds, travel, home renovations, and automotive expenses, however, they are replaced by a pattern of saving for no purpose at all.

This enduring saving propensity is rooted in long-standing saving habits and an absence of retirement role models, which provoke anxiety and impede effective financial management. Acknowledging this life-costs pattern help embed a more realistic and balanced approach to financial planning in later life.

Where next?

We find ourselves at a pivotal crossroads where traditional approaches to navigating the complexities of money in later life are being redefined. Perennials are a diverse group with a wide range of needs, preferences, and financial circumstances and increasingly a one-size-fits-all approach is unlikely to resonate. Our 'new abnormal' era challenges us to rethink our traditional financial solutions of how to serve our ageing population's dynamic needs.

At an individual level, as time inevitably advances, all of us have already or will be transitioning into the older citizens of tomorrow. As we age, our needs for financial products and services change, demanding that we take proactive steps to secure well-being during extended retirement years. Tailored strategies, aligned with long-term goals and personal risk tolerances, are crucial to acknowledging the non-linear experiences and financial realities of later life.

In common with all generations, financial literacy is an ongoing concern, yet it is often focused on younger generations. It's just as essential for older adults to navigate complexities of money in retirement. A fresh approach to provision of educational resources could cover areas such as ‘whole retirement’ planning, investment management, fraud prevention and digital banking.

Access to affordable, personalised financial advice is key, given the intricate nature of retirement planning. Financial advisors can assist individuals and families navigate the complexities of the U-shaped spending curve, long-term financial strategies, probable healthcare expenses and intergenerational wealth transfer.

A primary challenge for industry is to move beyond categorising them into a singular group: everyone over a certain age, usually retirement age. This approach often assumes that individuals from 60 to 100 years old and beyond have similar experiences and mindsets. More granular life-stage based segmentations may offer potential for enhanced targeting of financial products and delivery of both ‘brilliant basics and’ personalised experiences. In particular, the intersection of financial considerations and healthcare needs could open new opportunities for cross-sector solutions such as integrated platforms that coordinate healthcare payments, insurance claims, and financial advice.

Ultimately the ageing population presents both commercial and reputational opportunities. A chance for businesses across the whole sector to maximise customer retention and make a wider societal impact. By developing products and services that cater to the needs of older adults, businesses can improve well-being, foster independence, and contribute to a more inclusive society for all.

References

- Household Below Average Income, 2021/22 DWP, UK Poverty 2024: The essential guide to understanding poverty in the UK | Joseph Rowntree Foundation

- U.K Life Expectancy 1950-2025

- Aviva, Planning for Retirement in the 2050s. An online survey of 3,000 adults aged 18-75 across the UK, which was conducted by Ipsos on behalf of Aviva. Base of pre-retired for ideal retirement age: 2,467. Fieldwork was conducted in March 2023

- Aviva, Planning for Retirement in the 2050s. An online survey of 3,000 adults aged 18-75 across the UK, which was conducted by Ipsos on behalf of Aviva. Base of pre-retired for ideal retirement age: 2,467. Fieldwork was conducted in March 2023

- Only 48% of individuals aged 58 to 75 express optimism that 2025 will be a better year than 2024, with just 27% believing the global economy will be stronger, in stark contrast to younger age groups between 16-57. Additionally, a significant 89% of the 58-75-year-olds agree that taxes in the UK will rise compared to 2024. Source: Ipsos Prediction 2025, a survey of 1,000 adults aged 16-75 conducted in Great Britain from December 13th to 17th, 2024

- Ipsos, Financial Research Survey (FRS) for the 12 months ending April 2025. The FRS surveys a sample of around 50,000 adults (aged 16+) a year in total across Great Britain, interviews take place over the phone and online, taking into account (and weighted to) the overall profile of the adult population

- Ipsos, Housing Preferences for Older People. Survey of over 5,591 UK residents aged 50 and over, using Ipsos' Knowledge Panel, a random probability survey panel with selection based on a random sample of UK households. Base: All those who moved to a smaller or cheaper property in the last 5 years (301). The fieldwork was carried out between 7th December – 13th December 2023