What do the World Cup and Scottish Referendum have in common?

Watching the World Cup turned into a bit of a chore for my friends and family this summer. About twenty minutes into the first England match Wayne Rooney lined up the ball to take a free kick and the referee sprayed disappearing foam on the ground to stop the defending team encroaching. “It’s a feedback mechanism”, I declared, “it’s a behavioural economics intervention in action”. The room groaned, and my friends didn’t watch many other matches with me afterwards.

Behavioural insights and interventions are becoming more commonplace, partly because people are understanding the application of behavioural economics, and partly because the behavioural economists are getting better at explaining themselves. The geeky blogs that I frequent were much quicker than me to write about how the classic intervention of Feedback, Reminders, and Self-control were being used on the football field. One blog even suggested we need more interventions like these just to boost the support and morale of referees in the game.

Behavioural insights and interventions are becoming more commonplace, partly because people are understanding the application of behavioural economics, and partly because the behavioural economists are getting better at explaining themselves. The geeky blogs that I frequent were much quicker than me to write about how the classic intervention of Feedback, Reminders, and Self-control were being used on the football field. One blog even suggested we need more interventions like these just to boost the support and morale of referees in the game.

Interventions, biases, heuristics, and other phrases from the behavioural sciences are becoming ubiquitous in market research as we seek to understand and categorise the irrational manner in which the brain works. This categorisation is helping us understand why behave the way we behave; because we don’t always understand it ourselves. Evidence clearly suggests that there is a fast part to our brain (System 1 to use Kahneman’s language), that likes to act without waiting for justification, and a slower part to our brain that seeks to report what we have just done to the wider world (System 2).

Think about in terms of journalism; journalists are your system 2. Your system 2 thinks about life, pontificates a bit and then realises that it needs to report what’s just happened. It then chooses which story to report on while discarding numerous others, and then takes an angle on how to report the news. Indeed, you might even create two or three different versions of the same event depending on the situation, such as “I didn’t take my medication because I forgot” to the doctor, or “I didn’t take my medication because I don’t think it will work” to friends. Meanwhile your System 1, fast thinking brain is just doing.

Following the news, not reporting the news

The World Cup wasn’t the only place I bored people with behavioural economics; the Scottish referendum was awash with behavioural biases. First of all, the question had to be amended on our recommendation from ‘Do you agree that Scotland should be an independent nation’, to ‘Should Scotland be an independent nation’ because of the inherently leading opener. Once the question was set, the No campaign rightly changed their name to Better Together; people don’t like to cast a ‘No’ vote.

But the bigger biases came from the campaigns themselves, with the Better Together camp playing heavily on Loss Aversion. The campaign message was Scotland would have a lot to lose by voting for Independence, and the message hit a particularly nerve when the Scots were told they would lose their currency. Money is clearly a salient message for Scots. The Yes campaign were pulling on the identity biases wherever they could, most strongly on In-Group bias to unite Scotland against the others. Salmond’s identity politics meant he had to draw a line between us and them, and when he painted ‘them’ as Westminster politicos his message resonated with the Scottish electorate.

But the bigger biases came from the campaigns themselves, with the Better Together camp playing heavily on Loss Aversion. The campaign message was Scotland would have a lot to lose by voting for Independence, and the message hit a particularly nerve when the Scots were told they would lose their currency. Money is clearly a salient message for Scots. The Yes campaign were pulling on the identity biases wherever they could, most strongly on In-Group bias to unite Scotland against the others. Salmond’s identity politics meant he had to draw a line between us and them, and when he painted ‘them’ as Westminster politicos his message resonated with the Scottish electorate.

Outside of politics, advertising agencies often get behavioural economics intrinsically. Dior recently launched a line of comfy shoes. Fighting the prevailing belief that most trainer type shoes are mass produced in large factories abroad, potentially under poor labour conditions, Dior used the Effort heuristic to increase the perceived value of the shoe. The advert shows the finest craftsmen in Paris carefully placing the stitches and beads with exacting precision, the soles being moulded by engineers, and even the laces were hand crocheted. With Dior, you are buying effort with every shoe.

Outside of politics, advertising agencies often get behavioural economics intrinsically. Dior recently launched a line of comfy shoes. Fighting the prevailing belief that most trainer type shoes are mass produced in large factories abroad, potentially under poor labour conditions, Dior used the Effort heuristic to increase the perceived value of the shoe. The advert shows the finest craftsmen in Paris carefully placing the stitches and beads with exacting precision, the soles being moulded by engineers, and even the laces were hand crocheted. With Dior, you are buying effort with every shoe.

The behavioural sciences do not just apply to communications, there are a whole host of applications in product usage and design. Financial services providers were quick to create an Affect heuristic through allowing customers to put a picture of their loved one on their credit cards in an attempt to induce an emotional connection when spending. Supermarkets have used the principles of Reciprocity to encourage people to spend more time in-store. Consumer goods companies are using behaviour change principles in laundry, personal care, and even with air fresheners.

The behavioural sciences do not just apply to communications, there are a whole host of applications in product usage and design. Financial services providers were quick to create an Affect heuristic through allowing customers to put a picture of their loved one on their credit cards in an attempt to induce an emotional connection when spending. Supermarkets have used the principles of Reciprocity to encourage people to spend more time in-store. Consumer goods companies are using behaviour change principles in laundry, personal care, and even with air fresheners.

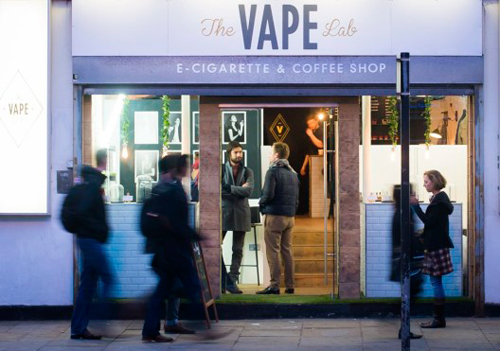

Proponents of e-cigarettes are trying to find ways to make their product more habitual. Consumer attempts to quit smoking should be relatively straightforward in a rational, logical sense when the smoker wants to quit. However, this attempt to reengineer a rational argument to fit an emotional disposition doesn’t work, and smokers aren’t yet taken with e-cigarettes as a suitable substitute – over two thirds of e-cigarette smokers still smoke cigarettes. Every cigarette relates to experiences; smoking is not so much an addiction as a habit. After a few years of smoking, it is the associations, actions and mannerisms we crave more than the drug itself, and let’s be frank, the smoker ‘scene’ for e-cigarettes doesn’t make you part of the cool club.

Proponents of e-cigarettes are trying to find ways to make their product more habitual. Consumer attempts to quit smoking should be relatively straightforward in a rational, logical sense when the smoker wants to quit. However, this attempt to reengineer a rational argument to fit an emotional disposition doesn’t work, and smokers aren’t yet taken with e-cigarettes as a suitable substitute – over two thirds of e-cigarette smokers still smoke cigarettes. Every cigarette relates to experiences; smoking is not so much an addiction as a habit. After a few years of smoking, it is the associations, actions and mannerisms we crave more than the drug itself, and let’s be frank, the smoker ‘scene’ for e-cigarettes doesn’t make you part of the cool club.

So we shouldn’t be surprised at the arrival of ‘vaping shops’, the latest attempt to create an experience through a Social Incentive. They are a place for people to go, where people conform to the same identity, and reinforcing each other’s ‘vaping’.