Data Dive: Coronavirus crisis leaves scars, lessons in its wake

You only truly see the damage a ferocious storm makes once the rain and the wind have stopped.

And so it is with the coronavirus crisis.

It’s been four long years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global health emergency on March 11, 2020, sending much of the world’s population into isolation.

What did social distancing and masking for weeks, months and in some cases years on end do to us individually and collectively?

The ultimate toll of living through this once-in-a-century event has yet to be truly tallied. But, as the world marks the fourth anniversary of the start of the pandemic we dive deeper into what Ipsos Global Advisor polling tells us about where we’ve been and where the data suggests we’re going.

What goes up must come down

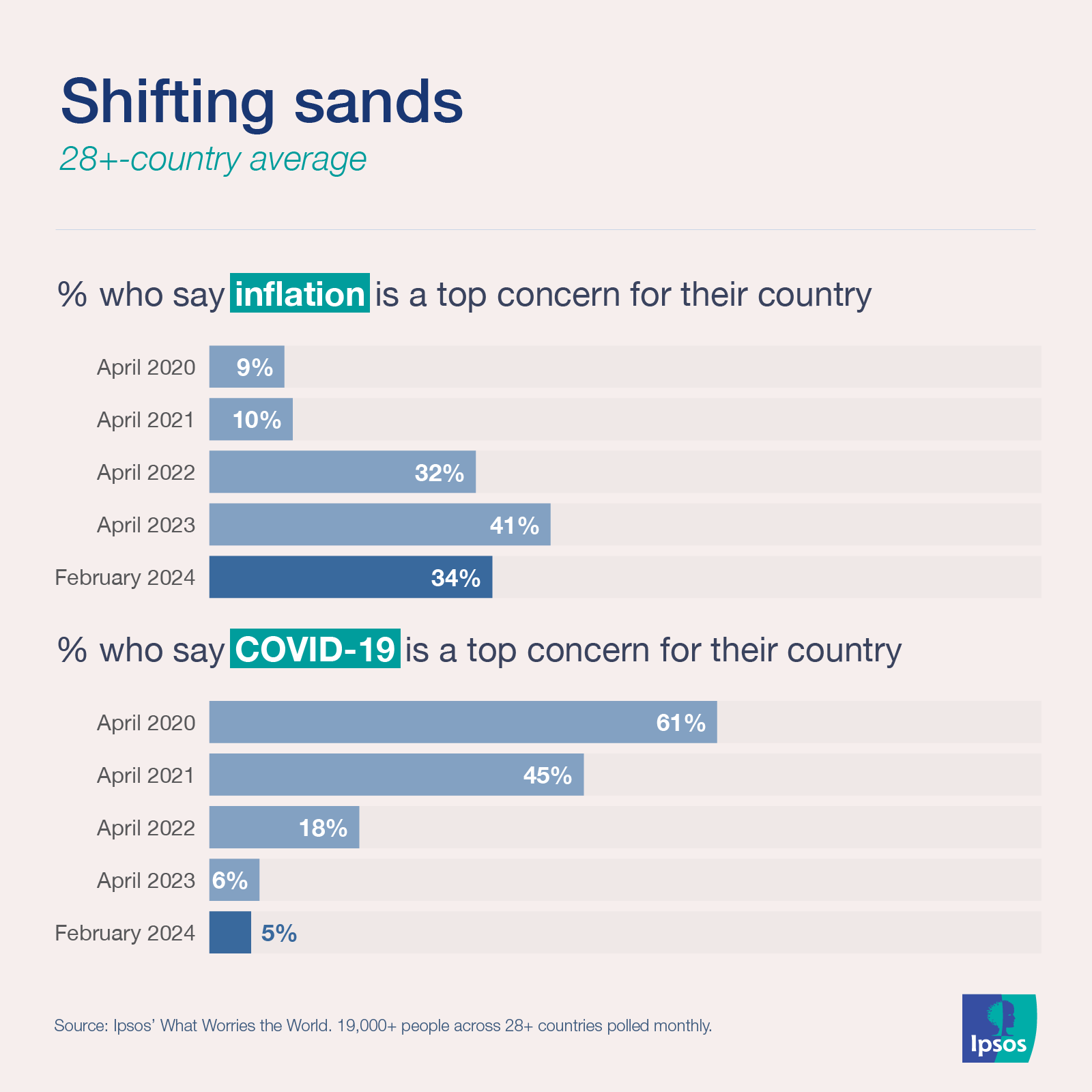

From the very start the coronavirus crisis was not only a health emergency, but also an economic earthquake that shook up economies around the world.Understandably, COVID-19 overshadowed all other issues at first but as lockdowns eased worries turned away from getting sick to sticker shock.

Back in April 2020 a mere 9%, on average across 28 countries, considered inflation a top concern for their country. By April 2022, as people were starting to get back to their pre-pandemic lives (and spending habits), concern about the cost of living more than tripled to 32% and ultimately peaked at 43% in February 2023. While inflation worry has now eased a bit to 34%, it’s still 25 percentage points higher than it was at the onset of the pandemic.

Like many people around the world, inflation wasn’t on most Poles’ radar in the spring of 2020 but concern has soared in recent years, going from 15% in April 2020 to 46% in February 2024.

Red-hot inflation is cooling in Poland, along with several other countries, but Poles are still feeling the sting of both high prices and high interest rates in the wake of the coronavirus crisis, followed by the full-scale invasion of Ukraine in early 2022.

“Over the last two decades the inflation level has remained very low, but in 2022 it increased significantly and in 2023 Poland had one of the highest inflation rates in Europe,” says Anna Karczmarczuk, Managing Director for Ipsos in Poland. “People felt this very strongly because the cost of living increased significantly (every-day shopping, energy costs, fuel), interest rates were raised and, consequently, the costs of loans became unavailable to many people.”

Long, winding road to recovery.

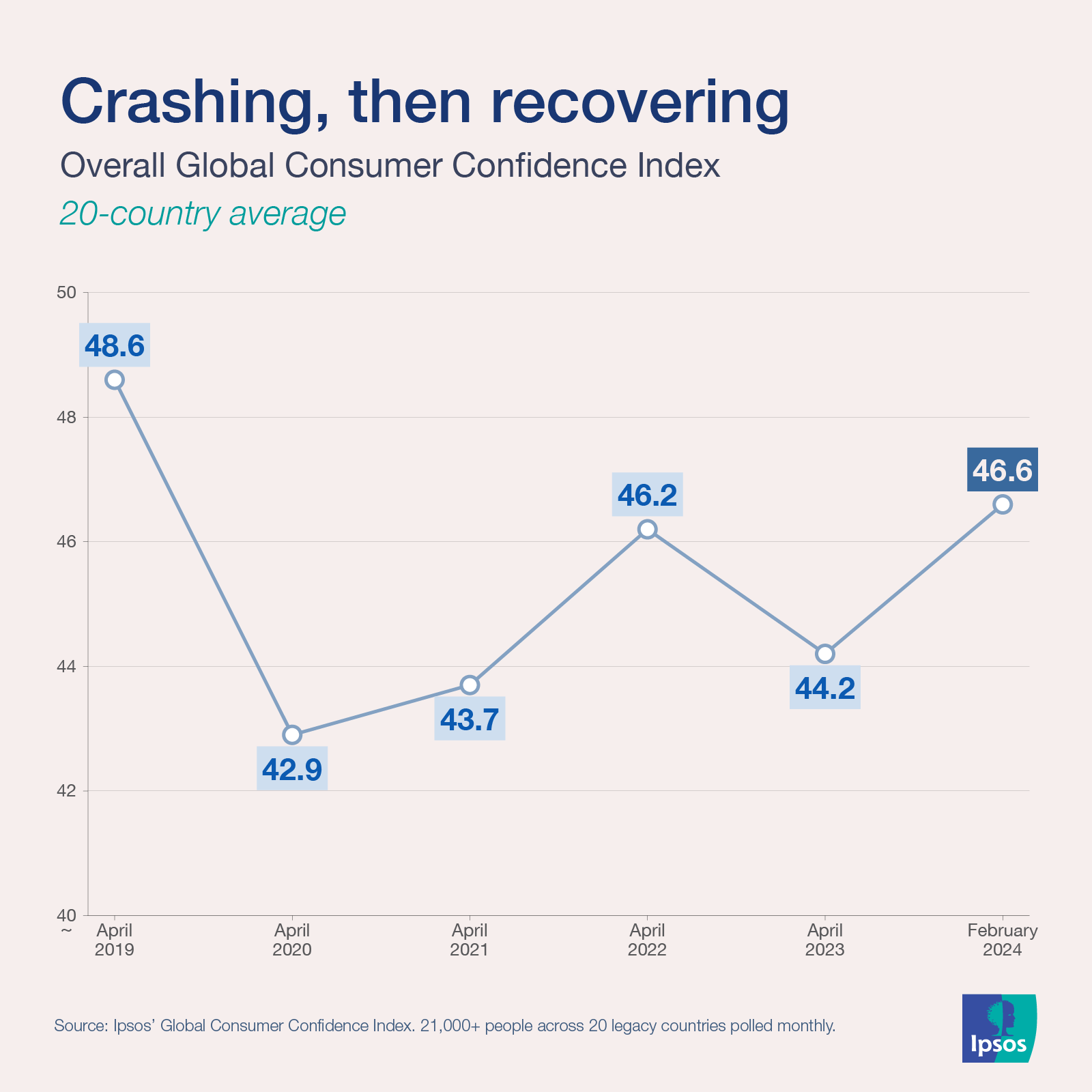

Things weren’t always this way.Four years ago many experts were rightfully worried that mandating people stay at home and forcing in-person businesses (such as salons, restaurants and theatres) to temporarily shut their doors could plunge the world into a severe economic downturn. Given the scary warnings from economists it’s little surprise global consumer confidence dove to historic lows during this uncertain time.

But by April 2021, with a bevy of government loan programs and central banks shoving interest rates to historic lows around the world, another Great Depression was averted and global consumer confidence was well on the road to recovery.

Prices rose alongside confidence but that didn’t stop some from shelling out like there was no tomorrow by splurging on everything from pricey trips to fancy meals (which some termed “revenge spending”) as lockdowns/restrictions eased.

Despite the world economy being slammed yet again in February 2022 with the full-scale invasion of Ukraine consumer confidence stayed relatively steady, though the unexpected stubbornness of inflation led to a dip in 2023. Global consumer confidence is currently near, but not quite, at pre-pandemic levels.

Though many Poles are still worrying about inflation national consumer confidence in Poland is now above where it was in the very early days of the coronavirus crisis (51.1 in Feb. 2024 versus 42.6 in April 2020).

This confidence echoes a general sense of optimism in the wake of the fall 2023 elections, says Karczmarczuk. “These elections were very important, we achieved record turnout and as a result, after eight years, there was a change of the ruling party in Poland. A large part of society perceives this optimistically and has high expectations of positive changes in the near future.”

And with inflation expected to further moderate in 2024 there’s been “a large increase in the number of respondents expecting an improvement in the economic situation and their own financial situation in the future. Many may feel that the crisis has been at least partially contained.”

Mental health steps out of the shadows.

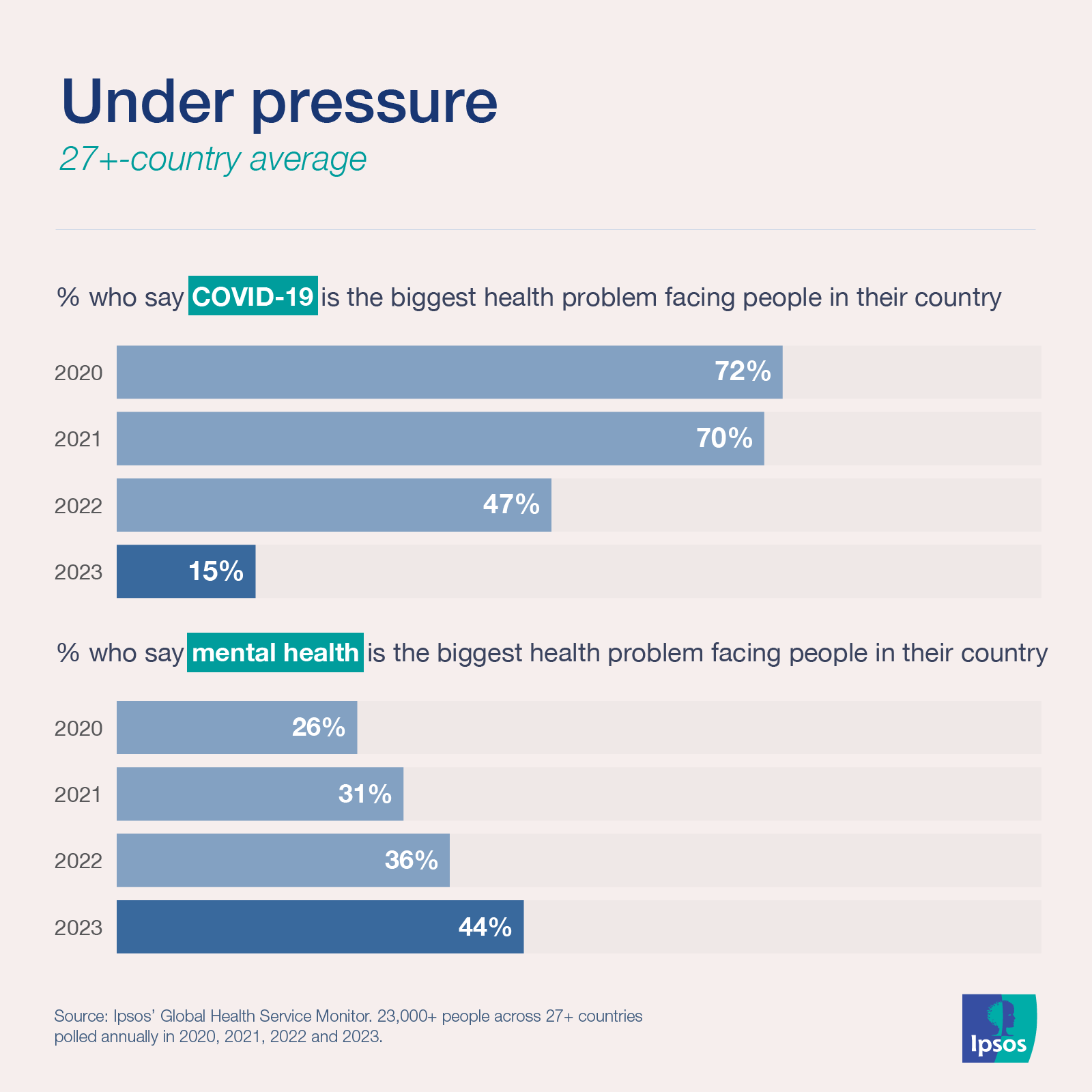

While consumer confidence is up these days, so is concern about mental health.During the first year of the crisis, COVID-19 loomed well above all other physical and emotional health issues. In the intervening years the proportion who consider COVID-19 the biggest health problem facing people in their country has plummeted as concern about mental health ticked upwards to become the No. 1 problem, on average across 31 countries in 2023, followed by cancer and stress.

Living through the so-called polycrisis (the pandemic, plus high inflation, plus the invasion of Ukraine etc.) has clearly exacted an emotional price on many of us — in particular young women.

One of the silver linings of the past few years was the increase in open discussion about mental health. Yet, it remains to be seen if all that talk will lead to sustained action to help people recover from the polycrisis and the crises yet to come.

Another one?

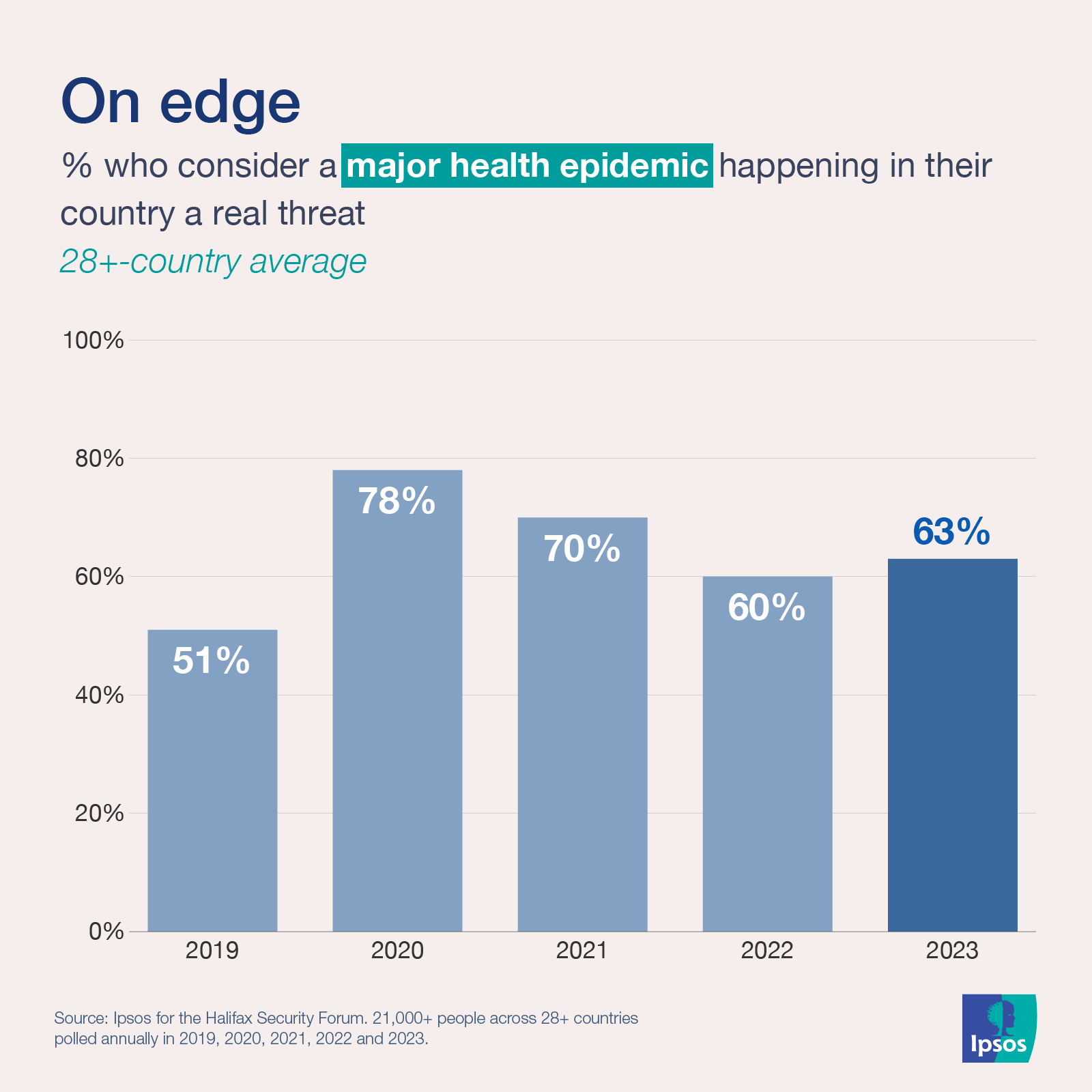

One sign that the COVID-19 pandemic has left its mark on our collective psyche is our heightened concern about epidemics.In 2019 just over half of people, on average across 28 countries, considered an epidemic to be a real threat and that unsurprisingly soared to 78% in 2020.

While worry about an epidemic has dropped a fair amount in the intervening years concern remains 12 points higher than it was pre-pandemic.

Like some other countries anxiety about an epidemic is higher than it used to be among people in Mexico (59% in 2019 vs. 65% in 2023).

Laura Romero, Head of Healthcare, for Ipsos in Mexico says while the darkest days are behind us the stark memories stay.

“COVID-19 had a great impact on people, almost everybody had someone that was affected. People are aware that the patients more affected are those with metabolic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, etcetera, and these diseases are very prevalent in Mexico — so people feel at risk. In addition, the health system in Mexico came under immense strain, with few free beds in the hospitals and lack of oxygen, generating panic during the pandemic.”

Loudest voices heard the most?

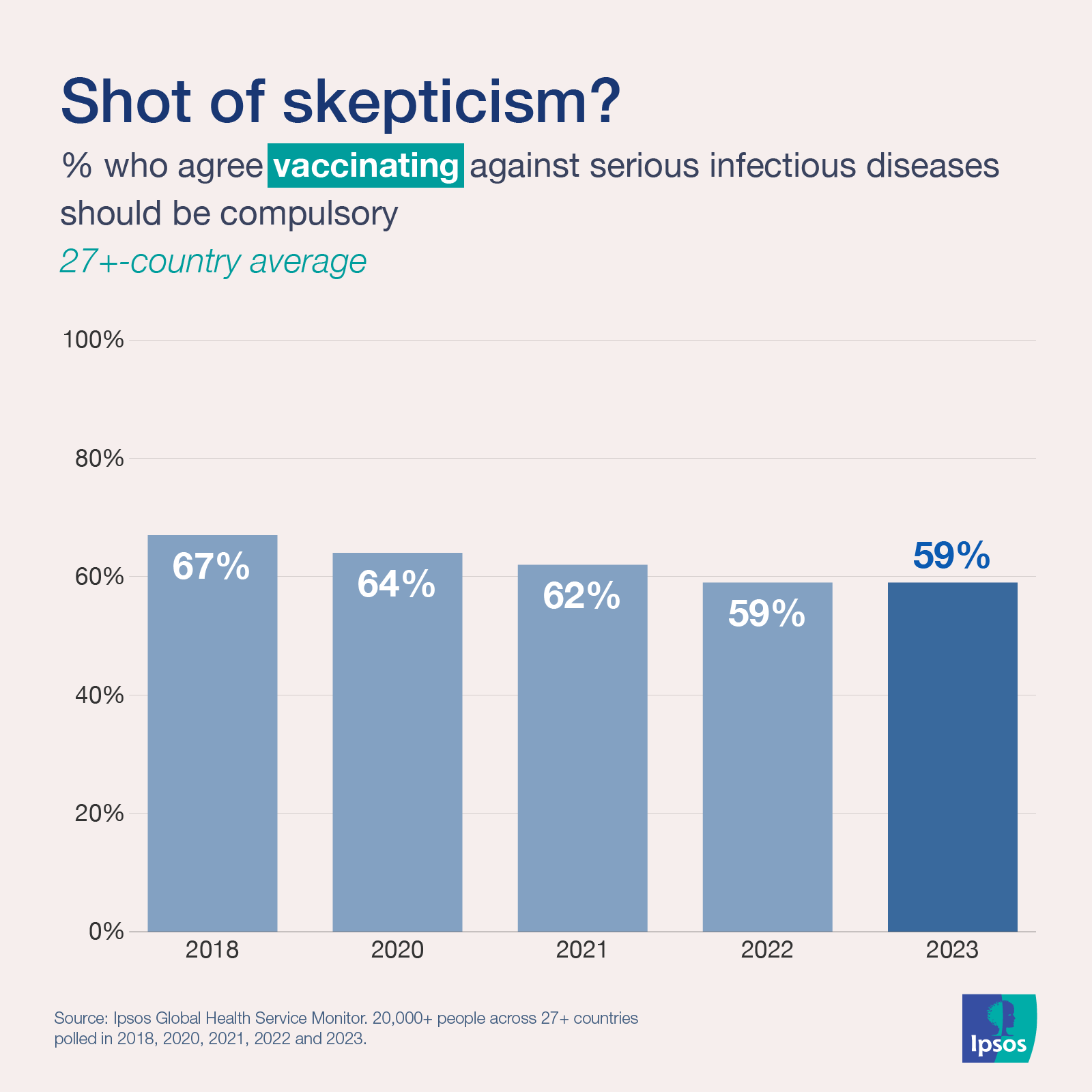

While pandemic-era street protests and social media at times made it seem like the public mood was turning against vaccine mandates, the reality is more nuanced.Our 2023 Global Health Monitor finds almost three in five (59% on average across 31 countries) agree vaccinating against serious infectious diseases should be compulsory. Support decreased a bit from 67% in 2018 to 64% in 2020, then 62% in 2021). Attitudes towards compulsory vaccines have since stabilized, sitting at 59% in both 2022 and 2023.

Some countries have seen significant decreases in support for compulsory vaccines, such as the U.S. (40% in 2023 vs. 53% in 2018). While others, such as America’s neighbor to the South, haven’t seen a drop.

In Mexico support for compulsory vaccines was quite high pre-pandemic (74% in 2019) and basically hasn’t budged (75% in both 2020 and 2021; 75% in 2022 and 2023).

“Vaccination used to be one of the strengths in the Mexican health system. Historically the coverage of vaccines in the public sector was very high and the schemes very complete compared to other LATAM countries,” says Romero.

But, despite consistently high support there’s been a drop in vaccinations in Mexico, adds Romero. “In recent years the coverage and the proportion of people vaccinated has reduced due to low availability of certain vaccines in the public sector, but people are aware of the benefits of vaccination.”