Americans agree with police reform, but defund the police currently a bridge too far

For weeks now, thousands of protests have taken place in large cities, small towns, and everything in between across the country. George Floyd's death in police custody sparked this outpouring of solidarity when a video emerged of a police officer kneeling on his neck for nearly 9 minutes as he dies.

Now, many Americans want to transform what law enforcement in the U.S. looks like. While there is an appetite for change, evident in both the non-stop protests and in the polling, the exact ways police departments should move on from here is less clear.

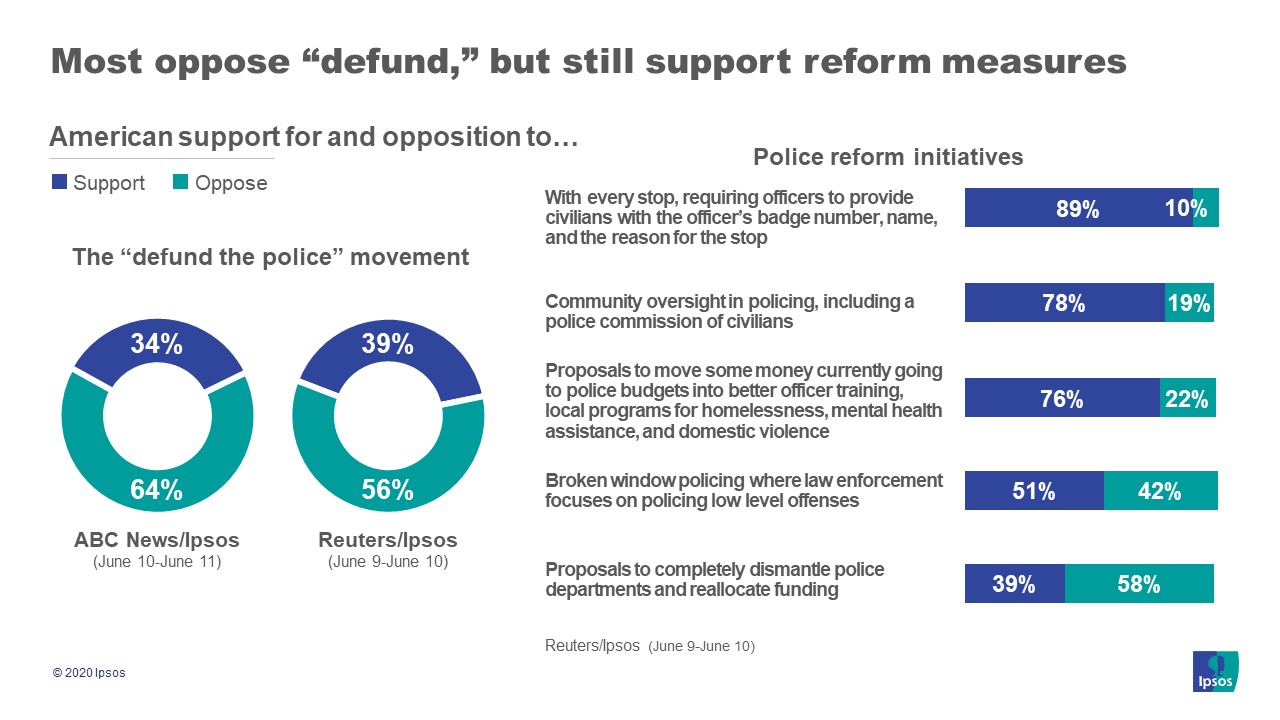

Most Americans oppose “defund the police”. Nearly two-thirds in a recent ABC News/Ipsos poll are against it, with Reuters/Ipsos polling finding similar breaks.

Though what defunding the police entails could mean many things depending on who you ask. For some, the phrase refers to completely dissolving police departments and redistributing their money.

Americans don’t seem to be too keen on that idea. Dismantling police departments entirely and reallocating funds does not win any majority. 58% oppose doing away with police departments in this way, similar to the share of people who oppose defunding the police.

Yet, many aspects of police reform that are part of “defund the police” have clear majority support. Three in four Americans (76%) support moving some money away from police budgets and reinvesting in officer training along with funding local programs for homelessness, mental health assistance, and domestic violence.

Beyond the question of how law enforcement should function, other police reforms win decisive majorities as well. Over three-in-four people (78%) support community oversight in policing, specifically oversight that involves community members sitting on police commissions to provide that check. 89% of Americans are behind officers providing their badge number, name, and reason they are stopping someone.

This data makes clear that the American public is broadly supportive of changing how the police function in communities, including reducing their budgets. However, at the same time, most people are hesitant to embrace a wholesale dismantling of local police departments.

This is a complete departure from the shape police reform took just two decades ago.

Broken windows policing was popularized during the last era of police reform. Officers were taught and incentivized to target low level offenses, like fare evasion or graffitiing public property, as a way of getting to and stopping more violent crime, like murder or theft. The hope was that interacting more with a community would allow officers to get better intel and start anticipating and preventing crime.

The results on whether broken windows policing was effective are mixed at best. In many instances, rather than enmesh officers into communities, it resulted in communities fearing punishment for minor offences. Yet, the public is still almost evenly split on their support for broken windows policing, indicating that many people don’t see the expanded power of broken windows policing and reforms of the defund movement as mutually exclusive.

Now, police reform is focused on preventing the number of interactions a heavily armed police officer might have with a community, particularly the black community, to limit the possibility for that power to be abused. But whether people back certain initiatives to reform the police has a lot to do with the messaging people hear. While ‘defund the police’ is still a vague idea, who defines that and how that takes shape in the public’s mind may drive whether those ideas come to fruition.