We need to talk about generations - Peak population

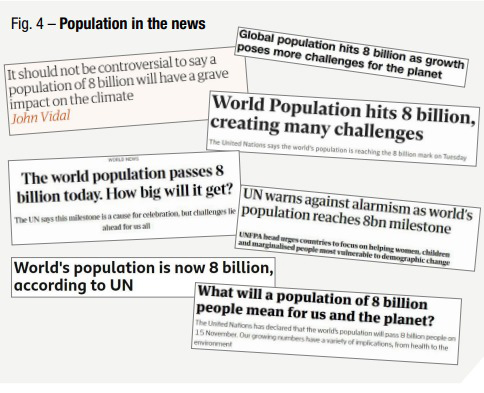

November 15th, 2022 was the “official day” when the world’s population topped eight billion. It took just 37 years for the number of people on earth to double from the four billion recorded in 1975.

November 15th, 2022 was the “official day” when the world’s population topped eight billion. It took just 37 years for the number of people on earth to double from the four billion recorded in 1975.

But, contrary to what you might think, world population growth is slowing down. In the words of the UN, “while it took the global population 12 years to grow from seven to eight billion, it will take approximately 15 years — until 2037 — for it to reach nine billion, a sign that the overall growth rate of the global population is slowing.”

Population superpowers: preparing for a fall

Although the trajectory is clear, we are witnessing something of a debate about whether India has already overtaken China or whether this is something about to happen. According to UN’s World Population Prospects 2022 Medium Variant, this milestone is set for 2023 as India’s population exceeds the 1.42 billion mark and China’s starts to fall.

Although the trajectory is clear, we are witnessing something of a debate about whether India has already overtaken China or whether this is something about to happen. According to UN’s World Population Prospects 2022 Medium Variant, this milestone is set for 2023 as India’s population exceeds the 1.42 billion mark and China’s starts to fall.

Together, these two population superpowers currently comprise 36% of the world’s population. They may have very different histories and cultures, but when it comes to their population journey, they are now on the same track, albeit at different stages.

China’s falling fertility rates are now well documented and stand at 1.18, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. Earlier this year, we saw a flurry of media coverage as journalists described the news that the population of China is now falling, for the first time in 60 years.

China’s falling fertility rates are now well documented and stand at 1.18, well below the replacement rate of 2.1. Earlier this year, we saw a flurry of media coverage as journalists described the news that the population of China is now falling, for the first time in 60 years.

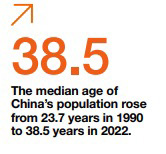

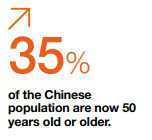

China’s population is now ageing very fast. The median age of its population rose from 23.7 years in 1990 to 38.5 in 2022, and 35% of the Chinese population are now 50 years old or older.

Meanwhile, the rise in India’s population in absolute terms has drawn attention away from its own falling fertility rates. Indeed, India’s figures have declined more dramatically than China’s during the past 20 years, from 3.22 to 2.01, which means that its population could start decreasing before the end of this century.

Meanwhile, the rise in India’s population in absolute terms has drawn attention away from its own falling fertility rates. Indeed, India’s figures have declined more dramatically than China’s during the past 20 years, from 3.22 to 2.01, which means that its population could start decreasing before the end of this century.

Those countries which have had a low fertility rate for a longer period, like Japan, Italy or South Korea, are ageing even faster.

Italy’s shrinking population is only now starting to become a real issue, with some questions about the prospects for the long-term “survival” of a distinct Italian nation. The very shape of its population pyramid is striking, with its increasingly top-heavy features, set against a narrow base. Prime Minister Georgia Meloni says Italy is “destined to disappear” unless it changes.

Together, China and India currently comprise 36% of the world’s population. They may have very different histories and cultures, but when it comes to their population journey, they are now on the same track, albeit at different stages

Super-ageing societies

These changes all have very real implications in terms of how society and the economy operate. Around 36% of Italians under 30 are living in a single-person household, while just 50% have a driving licence. And, when they are employed (the youngest working age groups being three times more likely to be unemployed), they have on average had between four and five different jobs since they’ve entered the labour market. This points to an insecure, unsettled lifestyle.

Meanwhile, South Korea is experiencing similar issues, with an extremely low fertility rate (now at only 0.87) and ageing very fast – just 22% are under 25, and they are outnumbered by the over 60s (25.5%).

Lower fertility rates and ageing are increasing the relative size of the older generations in nearly all the big economies, and in some cases, they are becoming close to a majority in many of the key Asian and European markets. This raises questions around how modern societies treat the older generations – do companies, brands, employers, and politicians need to rethink how they focus their efforts? We pick up on these themes in the next chapter.

Population Decline: What can be done?

But the reality of falling populations is not limited to a few “outlier countries”. New analysis by Darrell Bricker and John Ibbitson identifies 36 countries which are losing population already, with more set to follow them.

The Bricker and Ibbitson review looks at the responses put in place by individual countries (such as Canada’s policy of encouraging immigration), or initiatives designed to maintain or boost fertility rates (as per the contrasting plans being adopted by Hungary and Sweden) and shows they may not achieve their goals.

They also raise what is now an urgent question, which centres on the economic consequences of ageing – the impact of fewer workers on the tax receipts that support public services, the impact of fewer consumers on spending power, the impact of fewer creative minds on our innovation pipelines.

In Empty Planet we wrote: Population decline is not a good thing or a bad thing. But it is a big thing. Four years on, we’ve changed our minds. We believe that population decline is a very bad thing, one that could define our future. If, that is, we have much of a future left.

— Darrell Bricker & John Ibbitson

Table of content

- We need to talk about generations: Understanding generations - Foreword by Ben Page

- Introduction: Generation myths and demographic realities

- Context: Why generational analysis matters

- Peak population: Preparing for the fall

- A topic of conversation: How do people talk about generations?

- Generation questions: Issues to think about

- How to tell a myth from a reality in UK generations

- Western generational concepts don't apply in South Africa

- Why where you live matters in understanding generations in India

- Super-ageing in post-pandemic South Korea

- Population bust: How Italy is finally facing its grey rhino

- Mexico: from a teenage country to an adult one in a century

| Previous | Next |

![[Webinar] Real evidence from real experiences: Patient Centric Evidence](/sites/default/files/styles/list_item_image/public/ct/event/2026-03/ipsos-webinar-real-evidence-real-experiences.webp?itok=i_Bx2O-9)