We need to talk about generation - Context

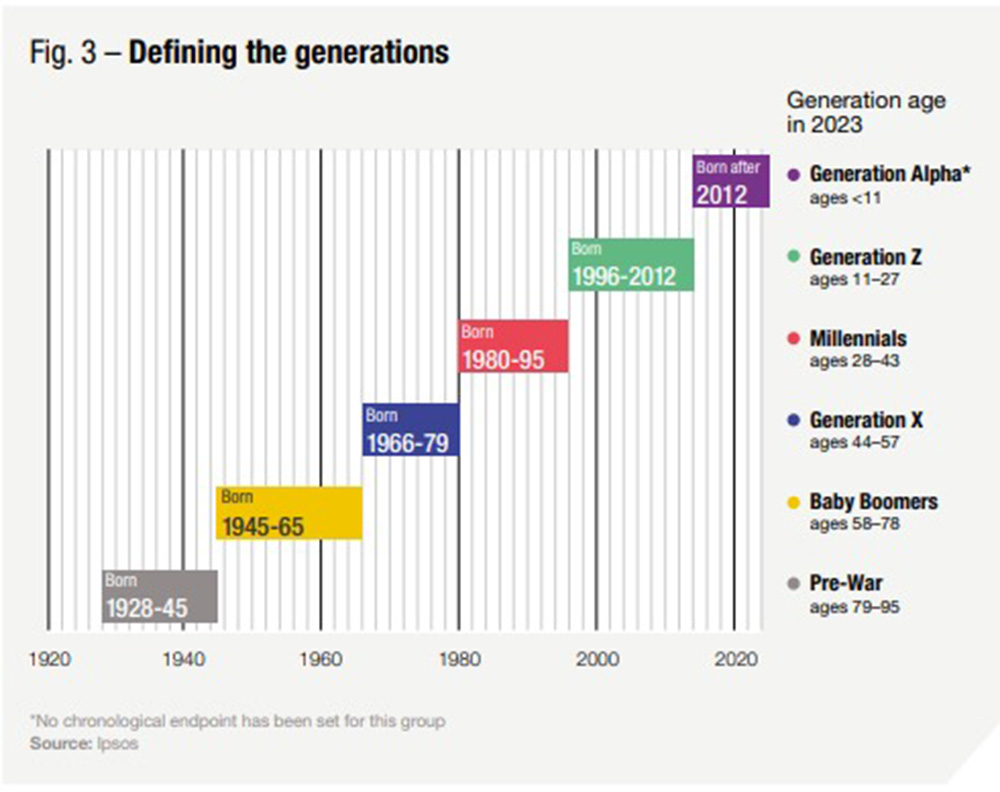

It’s easy to get swept up in the terminology of generations, as we enthusiastically describe the worlds of Generation Z, Millennials, Generation X, Boomers, the Silent Generation and – coming soon – Generation Alpha.

It’s easy to get swept up in the terminology of generations, as we enthusiastically describe the worlds of Generation Z, Millennials, Generation X, Boomers, the Silent Generation and – coming soon – Generation Alpha.

These cohort names are now widely used these days by researchers as a more exciting version of the age brackets we were all trained on.

But any assertion about generations does need to be considered carefully. We must be mindful that terms like Millennial carry a lot more implicit baggage than 27-42-year-olds.

When we use cohort names rather than age groups, we are making a subliminal statement that we believe what we are describing is a characteristic which is an enduring feature of the generation under question.

When used widely, they also suggest a level of uniformity of thought or behaviour among the group which is rarely accurate.

In search of data

Generational analysis is not easy. Not least because rigorous research on this topic relies on the availability of long-term data. Take the example of Generation Z. The evidence required to prove many of the statements that are made about them is often just not available – sometimes because the issues that matter to young people today were not considered important 10 or 20 years ago.

But generational analysis is most certainly worth the effort. Where we can see generational differences (and indeed similarities), they help us to understand what is going on now – and they also shine a light on how change happens in a society and unlock our ability to plan for the future.

When and where you were born matters

Much of the narrative on generations has its roots in analysis from the United States, as witnessed by the labels we are using, perhaps most notably Baby Boomers.

The more we’ve looked at this topic, the clearer we’ve become about the need to be very cautious about making too many generalisations about generations. We should not assume that our analysis, grounded in our own country’s experiences, is portable and can be uniformly explored across the world. When you were born and where you were born matter.

People born the same year but in different places will often have had very different experiences and trajectories. Consider two people respectively born in China and the United States in 1973. The formative experiences of today’s 50-year-olds, growing up in the 1980s, were rather different.

Generation X is my parents’ generation. Their growth environment, education background, and the changes brought to them in the wave of the whole era are quite different from mine. However, although young people in the city have gained better education and growth resources, we are still undergoing tremendous personal pressure in modernisation. The pressure is not the same as before. We squeeze in the subway, and bend over our phones wearing face masks, as we're faced with the challenge of a new social environment. This is totally different from that in the 60s, 70s, 80s and 90s.

— Gen Z, China

Source: Ipsos Ethnography Centre of Excellence

|

|

|

|

Building blocks for analysis

When faced with an apparent difference between generational cohorts, we tend to consider why this is the case through three lenses.

- Lifecycle effects: People’s orientations change as they age, driven by life stages or events. For example, they may travel (domestically or internationally) to find work, before getting married and having children. People’s incomes rise as they get older, and (in some countries at least), they will tend to accumulate savings.

- Period effects: Attitudes and behaviours of all cohorts change in a similar way over the same period. Our response to the pandemic could fall into this category and presents a rich seam for analysis. Not only did Covid affect people around the world, but it also generated a large amount of attitudinal and behavioural data to explore. At a more local level, different countries will have their own dynamics. As we show in our South Korea analysis, its “Generation X” are billed as the country’s first post-democratisation generation and display a unique set of characteristics.

- Cohort effects: A cohort has different views, and these stay different over time. These are perhaps the hardest for researchers to identify, but also potentially the most impactful, helping us do a better job at predicting future change.

Many of the misperceptions we see arise are from people mistaking a period or lifecycle effect for a true cohort effect

When we can carry out this kind of analysis effectively, we see that real shifts like decline in religious belief or loyalty to political parties, alongside acceptance of LGBT rights in many countries, are here to stay - but that other apparent trends like declining home ownership may (or may not) be shorter-lived.

When we can carry out this kind of analysis effectively, we see that real shifts like decline in religious belief or loyalty to political parties, alongside acceptance of LGBT rights in many countries, are here to stay - but that other apparent trends like declining home ownership may (or may not) be shorter-lived.

Many of the misperceptions we see arise are from people mistaking a period or lifecycle effect for a true cohort effect. Identifying what is a true cohort effect is therefore key to understanding how a generation may be different and will remain different as they age.

And, talking of ageing, we need to be clear, whenever we are making assertions about the implications of different generations’ attitudes or behaviours, about the broader demographic context. Because the younger generations may not be powering our societies and economies as much as received wisdom would like us to believe.

Take Italy as an example. When it comes to how old they are, the “average Italian” is not Generation Z, or even a Millennial. The median person in the world’s eighth largest economy is 48 years old, which puts them firmly in the little-written-about Generation X category. This is a group that has a lot of spending power and considerable influence across many aspects of people’s lives, including family, business, politics.

In the next sections, we pick up on these themes and set out some of the questions arising from our review, framed against the backdrop of the big demographic changes under way which will shape what happens next.

Table of content

- We need to talk about generations: Understanding generations - Foreword by Ben Page

- Introduction: Generation myths and demographic realities

- Context: Why generational analysis matters

- Peak population: Preparing for the fall

- A topic of conversation: How do people talk about generations?

- Generation questions: Issues to think about

- How to tell a myth from a reality in UK generations

- Western generational concepts don't apply in South Africa

- Why where you live matters in understanding generations in India

- Super-ageing in post-pandemic South Korea

- Population bust: How Italy is finally facing its grey rhino

- Mexico: from a teenage country to an adult one in a century

| Previous | Next |

![[Webinar] KEYS: What can we learn from what happened in 2025?](/sites/default/files/styles/list_item_image/public/ct/event/2025-12/keys-webinar-what-happened-in-2025-carousel.webp?itok=1gJKCCxx)