We need to talk about generations - A topic of conversation

What’s the prevailing mood around the world when it comes to how people feel about the different generations that comprise our societies, or indeed on their attitudes to population change?

Here we take soundings from 30 countries around the world, drawing on new survey data, and putting the spotlight on three topics that go to the heart of our exploration.

Freed from desire? The "ideal" family size?

Twice (in 2016 and 2022), we’ve asked people around the world what is the ideal number of children for a family to have – and across the countries we surveyed, on both occasions the overall answer was between 2.2 and 2.3: only slightly above replacement rate. This could indicate that there is hope for stabilising our population in the future. But, as always, there is devil in the detail.

Twice (in 2016 and 2022), we’ve asked people around the world what is the ideal number of children for a family to have – and across the countries we surveyed, on both occasions the overall answer was between 2.2 and 2.3: only slightly above replacement rate. This could indicate that there is hope for stabilising our population in the future. But, as always, there is devil in the detail.

While the decline in fertility globally over recent decades has been attributed to women becoming more educated and striving for lives providing more than just motherhood and domestic labour, it is notable that we found no significant gender difference in attitudes. There is no sense, in any country in our study, that men think families should be larger than women do. Nor do people who identify as “feminists” have a different opinion.

When we look at individual countries in the study, we can see the importance of culture, and also note some lasting effects of governments’ attempts to influence it. The three predominantly Muslim cultures in the survey express a stronger appetite for larger families. Typically, only a quarter of the people we asked said that having three or more children was ideal, but that number rose to 67% in Saudi Arabia, 61% in Malaysia, and 35% in Turkey.

At the other end of the spectrum, China was the lowest of all, with just 9% saying that having a larger family was ideal, a legacy of decades of limits on family size and of urbanisation. Clearly, there is an extraordinary amount of work to do if that country is to reverse its demographic collapse.

Looking at generational trends can also be illuminating. For example, we can see how in Japan and Korea, both countries with entrenched baby busts, the ideal number declines through successive generations – younger people in both countries express a much lower ideal than older people. Japan’s baby bust has been going on for longer, but Korea’s has been much steeper, and we see this mirrored in Koreans’ aspirations too. For every age group, the ideal also fell between 2016 and 2022. So, there is evidence in each case that ideals track reality down – ie that having smaller families becomes normalised because we see those who came before us (perhaps even our own parents!) having smaller families. It seems there is a compounding effect to demographic decline – that smaller families beget a desire for yet smaller families, and that there is a kind of momentum behind demographic decline that establishes itself in younger people’s minds. Expectations shape ideals.

What’s more, in every one of the countries that featured in our most recent study, the current fertility rate is already lower than the ideal number of children people tell us they want.

We've never had it so good? How i feel about my generation

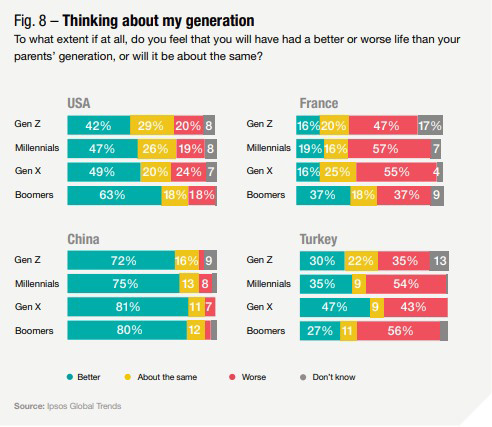

Just how are things now, compared to what went before? We asked people to tell us whether they feel they will have had a better or worse life than their parents’ generation.

Just how are things now, compared to what went before? We asked people to tell us whether they feel they will have had a better or worse life than their parents’ generation.

The results serve as a reminder that it is critical to ground our analysis in the context of where and when people were born.

In the US, we have a clear pattern. More than six in 10 US Baby Boomers acknowledge that they had a better life than their parents, while less than half (47%) of Millennials feel the same.

In France, the sentiment among Millennials is actively gloomy, with a majority believing they’ve had a worse life than their parents’ generation.

But this story is not replicated in all countries. When we look at Turkey, we find Baby Boomers to be the ones most inclined to say they had a worse life than their parents’ generation, while Generation X are significantly more satisfied, perhaps as a result of having benefited from the economic take-off of the 2000s.

The pattern in China is different again – with all groups saying their generation’s experience is better than the one that came before them. But it’s worth noticing that, again, Generation X are the ones who are particularly positive.

A new deal for older people? Assessing the mood

With the average age of populations on the rise in practically all countries, what do people around the world make of how people of different ages are treated these days?

With the average age of populations on the rise in practically all countries, what do people around the world make of how people of different ages are treated these days?

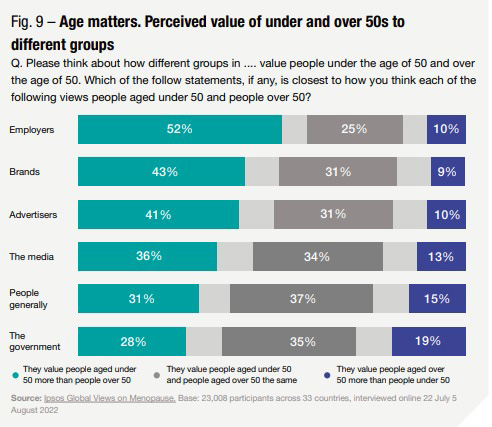

Here we find a real sense we live in societies that tend to value people under 50 rather more than they do older people.

Particularly stark is people’s assessments of what’s happening at work. A majority in North America, Europe, and Latin America (although not Asia or Africa) point to a bias among employers, who tend to value people under 50 more than older people.

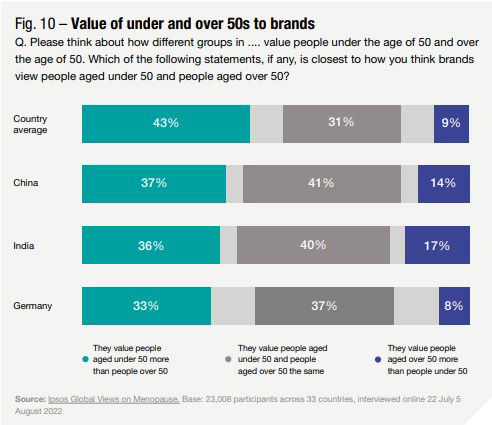

When we look at brands, we get a clear but nuanced picture. In almost all countries, there is a sense that younger people are valued more than older folk. In some countries we see clear majorities holding this view, but in other places the pattern is a little more textured. China, India, and Germany are three countries where there are a range of opinions on how people treat brands. Read the full 33-country report for more on the details for your country.

When we look at brands, we get a clear but nuanced picture. In almost all countries, there is a sense that younger people are valued more than older folk. In some countries we see clear majorities holding this view, but in other places the pattern is a little more textured. China, India, and Germany are three countries where there are a range of opinions on how people treat brands. Read the full 33-country report for more on the details for your country.

Table of content

- We need to talk about generations: Understanding generations - Foreword by Ben Page

- Introduction: Generation myths and demographic realities

- Context: Why generational analysis matters

- Peak population: Preparing for the fall

- A topic of conversation: How do people talk about generations?

- Generation questions: Issues to think about

- How to tell a myth from a reality in UK generations

- Western generational concepts don't apply in South Africa

- Why where you live matters in understanding generations in India

- Super-ageing in post-pandemic South Korea

- Population bust: How Italy is finally facing its grey rhino

- Mexico: from a teenage country to an adult one in a century

| Previous | Next |

![[Webinar] KEYS: What can we learn from what happened in 2025?](/sites/default/files/styles/list_item_image/public/ct/event/2025-12/keys-webinar-what-happened-in-2025-carousel.webp?itok=1gJKCCxx)