House prices: how good are people at predicting what's going to happen?

In his seminal Wisdom of Crowds, James Surowiecki challenged the preconception that experts know best, a view echoed by Professor Philip E. Tetlock who found experts’ forecasts only slightly better than throwing dice. Predictions are far from easy in a world of accelerative change and global uncertainty but they are important nonetheless, helping to create important social norms and momentum behaviour.

According to Halifax, the average house price in the UK in March 2016 was £214,811, up from £160,785 five years ago in April 2011 which was also the point at which Ipsos started a quarterly tracking survey on behalf of Halifax.

Our Mar House Price Index shows annual price growth at 10.1%. Ave. house price now £214,811 https://t.co/0dLTII6xhK #UKhousing #HPI

— Halifax Bank News (@HalifaxBankNews) April 7, 2016

The survey asks people what they expect the average UK house price to be in twelve months’ time with respondents given a benchmark price (the current average UK price) and shown a list of scenarios ranging from 15%+ rises to the same magnitude of falls.

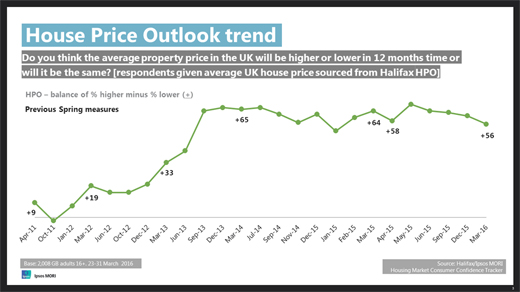

In 2011 32% expected prices to be higher in 12 months’ time while 23% thought they would be lower. Five years on, the equivalents were 65% and 9% and, over the period, people have become much more convinced that prices will rise. However, a closer look at trends shows that sentiment has been on a downward trajectory since a peak in sentiment in May 2015 (and against a backdrop of declining economic optimism). While the fall has been nothing like as steep as the rise in sentiment in autumn 2013, price outlook is clearly tracking downwards.

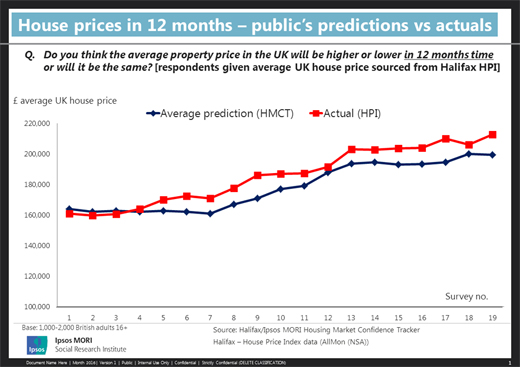

How good have people been at predicting movement in house prices? By averaging the distribution of predicted prices from the tracking survey and comparing these with Halifax’s monthly measure of actual prices, we find a strong correlation between predictions and subsequent market trends. Thus, it would appear that public expectations are a leading indicator of actual market movements.

We ought to be careful, though, because in terms of the percentage change in prices (rather than absolutes), the last six predictions of price increases have been half or less than half that of actual market increases. Further, our calculations use averages and even-out inaccurate predictions at either end of our scale (although, arguably, this is legitimate because Surowiecki identifies diversity as one of four preconditions for a group being ‘smart’).

We should also entertain the possibility that people might simply be reporting back what they are hearing in the media, the coverage of what the experts say will happen. For example, we have found the British public struggling to predict when interest rates would rise, perhaps unsurprising given, until recently, the vacillating nature of ‘forward guidance’.

Generally, we should also be wary of trusting the public’s predictive abilities if the ‘base case’ is the key basis for any prediction. Our ‘perils of perception’ work over the past few years has laid bare that the British have an odd (wrong) conception of their country. How can you predict the future, if you don’t know the present? But the British do have a comparatively good grasp of current house prices – even if they tend to underestimate the extent of house price rises in the past – and, anyway, the Halifax survey provides respondents with a benchmark price to ground predictions.

Another factor is likely to be the public’s appreciation of the impact of one of the key fundamentals in the housing market, namely the shortage of supply. While they do not always make the link between supply shortages and rising prices, the public agree rather than disagree by a margin of five to one that “unless we build many more new, affordable homes we will never be able to tackle the country’s housing problems”.

What next? Tellingly, the latest survey for Halifax sees a sharp rise in the proportion of people volunteering they ‘don’t know’ what will happen to house prices, chiming with suggestions that uncertainty could soften the market. On past form the public’s prediction of modest rises by the start of 2017 will bear out. But will they lose the knack during a potentially more volatile market? Their predictions are certainly worth watching.

Technical note

The tracking survey for Halifax involves interviewing c.2,000 British adults. Analysis is based on multiplying the number of respondents giving each price by the price (a mid-point for ranges, and the lowest point for the 15%+ ranges), and dividing by the number of respondents giving an answer (i.e. excluding don’t knows). The resulting average price was compared with the average price 12 months after fieldwork taken from Halifax’s HPI series (AllMon(NSA)). For both predictions and actuals, percentage changes were derived by comparing benchmark prices with the equivalents 12 months after fieldwork.

- Latest Halifax survey: On its fifth anniversary, Halifax survey finds dip in house price sentiment