Disruptive technologies: How data is collected when you can’t get on the ground

When Cyclone Idai hit Zimbabwe in March last year, it was one of the most devastating natural disasters to hit a country already reeling from the crippling effects of economic and climate shocks like drought.

When Cyclone Idai hit Zimbabwe in March last year, it was one of the most devastating natural disasters to hit a country already reeling from the crippling effects of economic and climate shocks like drought.

A state of disaster was declared by the government as hundreds died.

The World Bank estimates that 270,000 people were affected, with direct damages of US$622 million. That doesn’t include the estimated $1.1 billion needed for the rebuilding effort.

The Zimbabwean government asked the World Bank for support to conduct a Rapid Impact and Needs Assessment (RINA) after the cyclone hit. The global agency hired Ipsos to gather data remotely – an innovative solution for when you can’t put boots on the ground.

Washington, D.C.– based Ayaz Parvez is a Senior Disaster Risk Management Specialist with the World Bank’s Africa team, who’s been using remote sensing data since the devastating 2005 earthquake in Pakistan. He said there’s a sense of urgency in disasters to assess the damage quickly and efficiently – which is why they reach out to data analytics companies like Ipsos.

“If it’s a very dire situation, we act quickly to find the impacts and needs on the ground,” said Parvez. “These tools always help to form the Bank’s decisions together with the governments on how to design projects that can help people recover from such a crisis.”

The World Bank identifies 32 nations globally as fragility, conflict and violence (FCV) countries.

Added to that, a recent Ipsos' survey across 28 countries found the number of people who believed the world became more dangerous over the past year increased by 6% from 2018 to 80% last year. More people were also worried about the threat of a major natural disaster, and a violent conflict in their country in the next 12 months.

So, how does Ipsos gather data when it can’t get on the ground in fragile and conflict-affected areas?

Mark Polyak, Senior VP of Public Affairs in the U.S., has been using “disruptive technologies” like remote sensing in complex emergencies for clients like the World Bank to reduce uncertainty and assist in decision making during crisis.

What is remote sensing?

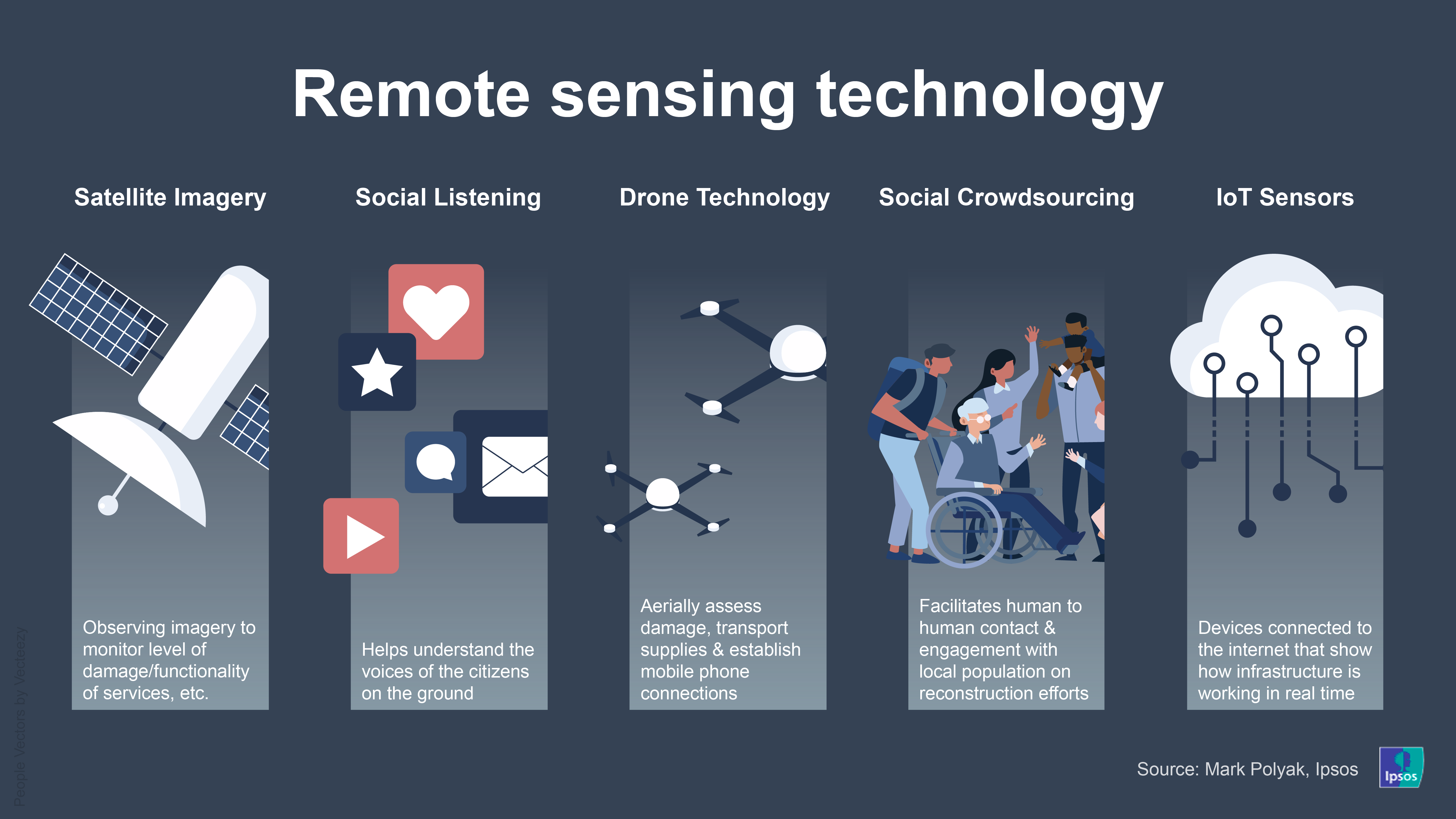

Polyak, who presented at the Consumer Electronics Show (CES) in Las Vegas this month on the subject, said the following five technologies are the most common types of remote sensing being used:

- Satellite Imagery – Is typically used to understand the level of damage/functionality of services as well as to forecast drought and/or infectious disease.

Polyak said the rise of nano-satellites and the rate of image collection in the last few years is turning the planet into a “real-time observation lab.”

“Current advanced satellite constellations provide six to eight daily revisit rates per area of interest, while some of planned satellite constellations, which are expected to be operational within next two years, promise between 40 to70 revisit rates per day,” said Polyak.

“This type of revisit rate will exponentially decrease bias in pattern detection based on one image at a time and allow ongoing crises and project monitoring.”

- Social Listening – Is used to understand the voice of citizens on the ground, and the availability and effectiveness of municipal services.

Polyak points out that this data is quite useful for qualitative insights from the ground, but needs to be used with caution. It comes with inherent biases on who has access to social networks in a conflict setting and can have cases of information distortion by conflict actors.

“Typically, these applications require advanced Natural Language Processing (NLP) algorithms to quickly filter or firehose the data,” he said.

- Drone Technology – Is increasingly used in a variety of complex natural disasters to efficiently and cost-effectively estimate impact. It provides much higher resolution and oblique angle images compared to satellites, but can’t typically be used in conflict settings by civilian agencies.

Polyak adds that drones can transport medical and construction supplies, establish cell phone connection in the middle of a disaster area, and assist in providing telemedicine.

- Social Crowdsourcing – Allows engagement with the local population to get input on planned activities, along with asking for ideas on innovative economic interventions. It helps to understand priorities for reconstruction.

“This technology can and should be used to facilitate human to human contact instead of replacing it,” said Polyak.

- Internet of Things (IoT) Senors – Increasingly, environmental, logistical, electrical and municipal service sensors are connected to the internet and allow for building an unprecedented picture of how cities/settlements’ infrastructure and services are working in real-time.

Impact of AI & cloud computing

While the use of remote sensing is increasing, Polyak said it’s becoming impossible to use this approach without cloud computing and artificial intelligence (AI) as our ability to store and analyze data grows.

“For example, the director of U.S. NGA (National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency) has publicly estimated that by 2037, it will need over eight million imagery analysts just to process, not to even analyze all imagery data. Obviously, that’s not feasible,” said Polyak.

“Cloud and edge computing allows for fast processing of both data and algorithms especially in emergencies, while AI is great for applying human-derived insights on a global scale.”

In the past five years, there’s been a surge in companies mostly focusing only on the development of algorithms for interpreting satellite imagery, IoTs or social media data.

“These types of algorithms would be great for humanitarian and crisis operations support, because many FCV countries need assistance in developing technical capacity, and infrastructure to conduct remote assessments themselves,” Polyak said.

What about privacy?

What about privacy?

But with the ability and demand now to see beyond snapshots of a crisis situation and provide continuous monitoring, there are also questions about how to protect the privacy of vulnerable people.

In a recent survey of nearly 19,000 people across 26 countries, just over a third (36%) said they trust organizations with how they handle their personal data, while only one in three people (35%) had a good idea of how much personal data companies hold about them, and what they do with it (32%).

Andrew Young, Knowledge Director of The Governance Lab at New York University, said data that’s been collected responsibly can still create risks and harm if shared with unauthorized parties or analyzed in a biased or faulty manner.

“The governance question over the exchange of data is still somewhat outstanding, though we are seeing experiments with a number of models, such as independent ethical councils empowered to determine what types of data collection or use are appropriate, involving institutional review bodies early in the process,” said Young, who leads research on the impact of technology on public institutions.

“The GovLab and UNICEF recently launched an initiative seeking to define the principles that can support practitioners in the responsible handling of data for and about children.”

Meanwhile, Polyak points out that the data he utilizes is always anonymized like surrogate cell phone IDs, and Ipsos only provides aggregated insights - meaning raw data is never provided to a client.

“We only provide analysis of large scale patterns… There’s no way for us to say this is that person,” said Polyak. “But the data is super useful in understanding service delivery, for example, in a developing place.”

By looking at the number of cell phones in a health facility, Polyak said he can estimate wait times for access to services.

“I can say that all the cell phones that stay here from 9am to 5pm are probably the phones of staff,” Polyak said. “Everybody who stays there less than an hour is probably a patient.”

Parvez of the World Bank agreed, saying they look at data in terms of the percentage of people who are deprived of certain services in a disaster.

“They are broad diagnostics, and we are not interested in geotargeting this information to the level of affected people in that way. We’re not using any particular type of data to describe a set of people or any sort of ethnicity,” said Parvez.

“In some cases that are qualitative, we have done our work anonymously, and I don’t think the privacy of affected communities or individuals is compromised.”